"Fall, will you, don't embarrass yourself for a spoonful of blood!" — words in Albanian of Maliq Pasha recorded in 1809

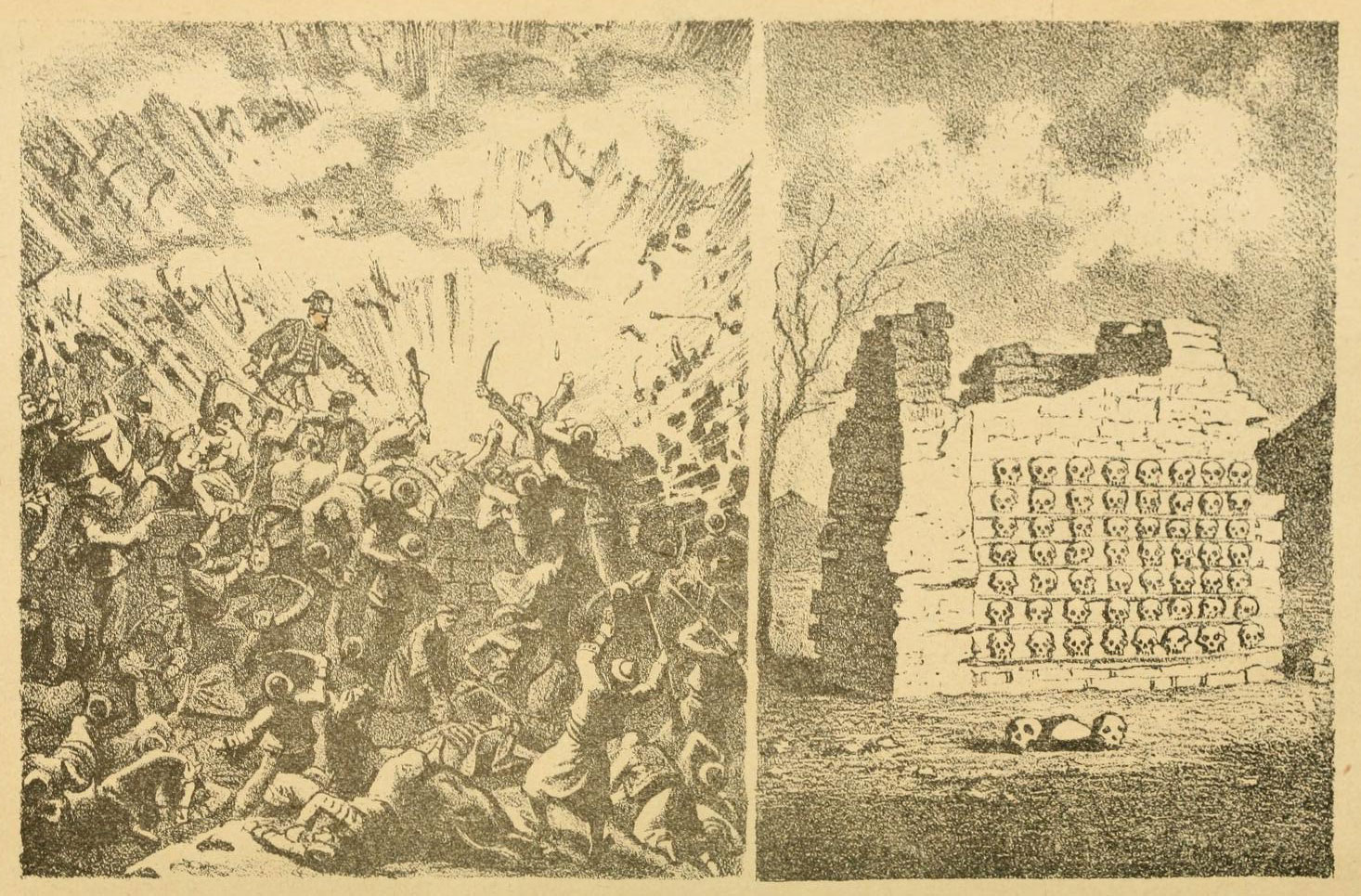

In a notebook of the Monastery of Saint Mark in Korishte near Prizren, in the notes of an abbot there, the words of Maliq Pasha were recorded in a battle against the Serbs that took place in Kamenica on May 31, 1809. The words were noted in Albanian using the Cyrillic alphabet and transliterated with modern Albanian alphabet, they come out like this: "Bini bre, mos [m]barohni prnj lugj gjak!" that translates as "Fall, will you, don't embarrass yourself for a spoonful of blood!".1 This is a rare case when we find the Albanian language registered in Kosovo, and that from the mouth of one of the main leaders of this period.

Writings in the Albanian language in Kosovo, before the 20th century, are few. The earliest we find are some words collected by Pjetër Mazreku, who writes from Prizren to Propagana Fides in Rome for the Albanians.2 Somewhere around 1650, Ndre Bogdani, probably in Janjevë, compiled a grammar of the Albanian language, the manuscript of which was lost by his nephew Pjetri, while he was taking refuge in the mountains during the Great Turkish War (1683–1699). 3 Pjeter Bogdani himself sometime in 1675 wrote his great work Ceta e Profetve in Kosovo, and it was published several times, first in Padova in 1685, then (after Pjeter's death) in Venice in 1695 and 1702.4 In the following century, Albanian in Kosovo also begins to be written in Arabic letters, a Sylejman Shehu from Rahovec (1731-1771) writes an Albanian poem in Rahovec or Prizren. 5 Then in 1743, Gjon Nikollë Kazazi from Gjakova published his Albanian catechism in Rome. Around 1780, Mulla Dervish Peja also wrote some Albanian verses in the Arabic alphabet, this time in Peja. 6 Meanwhile, around the year 1800, a Mulla Beqiri also wrote in Albanian in Drenica.

The Albanian sentence of Malik Pasha Gjinolli from Prishtina is the earliest attestation of the Albanian language that was spoken in Pristina, although it was not written by the hand of this Pasha himself. Several other letters have been preserved from the Prishtina pinjolli, all written in Ottoman, and some of them are kept in the form of copies even today in the Archives of Pristina.

-

1

In the recording given, it is clear that the scribe, Aksentije Igumanov (1780–1825), abbot of the monastery of Saint Mark in Korishë near Prizren, had no experience with writing the Albanian language. He writes it like this: 'бини бре, мосе барохни, прњ љуђ ђак,' which in today's Albanian alphabet can be overwritten like this, 'bini bre, mose barohni, prnji lugj gjak.'

-

2

Injac Zamputi (2018). Relations and documents for the history of Albania (1610–1650). St. Gallen-Pristina: Albanisches Institut Faik Konica. doc. 37.

-

3

Peter Bogdani (1685). Cvnevs Prophetarvm De Christo Salvatore Mvndi, Et Eivs Evangelica Veritate. Vol. 1. Padova: Tipografia del Seminario. Preposition: To receive before the literary.

-

4

Yll Rugova (2022). Albanian typography 1555–1912. Pristina-Tirana: Varg and Berk. p. 103–109.

-

5

Nehat Krasniqi (2003). Traces of the origins of alhamido Albanian literature. In Islamic Education (71), 83–84.

-

6

Irakli Kostallari (1990). The popular basis of the literary language and the so-called purism. Philological Studies (3), p. 9–10.