Tracing the origin of Prishtina

Today the capital of the Republic of Kosovo, the city of Prishtina has a long history that can be traced back for 800 years, when this place originated. Prishtina arose in a complex historical context, in the center of Southeast Europe during the late Middle Ages. First as a large village and then as a city, Prishtina was conceived in the western territories of the Byzantine commonwealth. 1 The political and cultural world in which Prishtina was formed was the medieval Roman world, namely the Byzantine Empire, at that time of its decadence.

In the 13th and 14th century: Foundation and rise

Central lands in the Balkan peninsula where Prishtina was to be formed were inhabited mainly by Albanians, Bulgarians, Vlachs and Serbs, ethnic communities with a majority of the Orthodox Christian faith. The Byzantine imperial power, based in Constantinople, controlled the field of Kosovo through a military infrastructure with two centers, two garrison cities: Lypenion and Sfentzánion. We are talking about Lipjan and Zvecan. The latter had a fortress on a raised rocky hill, an image of which can be created from an engraving made by the Slovenian diplomat Benedikt Kuripešić, during his journey from Ljubljana to Constantinople in 1530, this engraving was published in his book of 1531, "Itinerary of the trip to Constantinople to the Turkish Emperor Suleiman". During the Serbian-Byzantine wars, after the battle of Pantina in 1170, the Grand Duke of Rashka, Stefan Nemanja managed to add Zveçan to his posessions. From this time, after the fall of Zveçan in the hands of the Serbs, Lypenion, namely Lipjani, as a field fortress, remained the main military point on which the Byzantine power relied on the plain of Kosovo.

At the end of the 13th century, the Vlachs and Bulgarians revolted and confronted the Byzantine power, led by the brothers Teodori and Aseni, from which arose what is known as the Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1422). Theodore, crowned as Peter II, ruled together with his brother Asen, but after the assassination of Asen in 1196, he made his younger brother Ivan, known as Kalojan, co-ruler, and when Theodore was also killed in 1197, Kalojan was left alone as the ruler of Bulgaria. In the spring and autumn of 1199, the Vlachs in alliance with the Cumans crossed the Danube and entered the territories of the Byzantine Empire. Taking advantage of this situation, Kalojani attacked the Byzantine lands and after several victories, managed to expand to the west, conquering Shkup and Prizren, among others. Thus, from the 12th century to the 13th century, the southern lands of the plain of Kosovo and the plain of Dukagjin were in the possession of the Bulgarians.

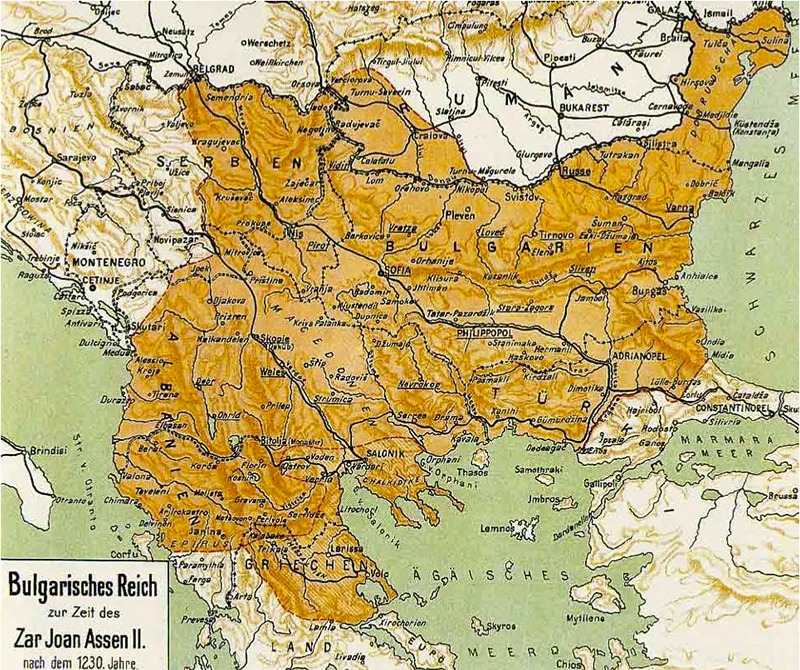

It was at this time, in 1202, that Pope Innocent III issued the consecration to the Catholics for a military expedition to take Jerusalem from the hands of the Muslims. This would be the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204). In April 1204, the Latin Crusaders took Constantinople from within, overthrowing the Byzantine imperial power in its metropolis. It was replaced by a crusader state known as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, and here began a period known as Francocracy, from the Greek "rule of the Franks", made up of the Catholic crusaders and their Venetian allies. The fragmented Byzantine power was divided into a trio with three centers: in Trebizond, in Nicaea, and in Epirus. This continued until July 1261 when the Empire of Nicaea recovered the Byzantine Empire and reinstated Constantinople as its metropolis. In the meantime, after Kaloyan's death in 1207, Bulgaria expanded even further under Ivan Asen II, as can be seen in the map below, made by the Bulgarian scholar Dimitar Rizov in 1917.

The Bulgarian Kingdom under Asen II until 1230. (Source: Atlas of D. Rizov, 1917)

The Bulgarian Kingdom under Asen II until 1230. (Source: Atlas of D. Rizov, 1917)

The weakening of Byzantine grasp created a power vacuum in the central Balkans, where during the 13th and 14th centuries, there were constant clashes and rivalries between the Bulgarians and the Serbian chieftains. The Serbian vassals made continuous incursions into the plain of Kosovo in the second half of the century. XIII. In the penultimate decade of the century XIII, King Stefan Milutin expanded his possessions in the direction of the Bulgarian ones, taking Prizren as well. In 1285, he built the fortress of Novobërda, necessary for the exploitation of the mining resources of the area. Arabs, Ragusans and even Saxon miners from Saxony gravitated to Novobërda, as the importance of this town grew until it became one of the richest cities in the Balkans of the late Middle Ages. This made Novobërda an important destination especially for silver merchants who traded it via the Adriatic across the Mediterranean.

At that time, the vegetation of Kosovo was much denser. The river valleys were filled with bushes and brambles, while the mountainous areas were much more wooded, as preserved in toponyms such as Lluga, Hvosno (Slavic: dense forest), Leskovc, Zabel, etc. But mining riches opened their own paths and created communication channels and trade routes. Thus, between the three mining centers, Janjeva and Novobërda in the south and Zveçan in the north, which was the guarantor of the minerals extracted from Trepça, there was a need for an intermediate center, which served as a stop for caravans, a station where the first horses were exchanged and where you were updated with road safety news and current events. Lypenion had completely lost its importance with the departure of the Byzantine power, so a few kilometers from this location, in a lowland, a new settlement was conceived: Prishtina!

For the name of this place, there are quite different variants circulating, from one to the other, up to the most surprising ones, the result of imaginary etymologies from intuitive curiosity. But the most likely explanation remains that of the American linguist Eric P. Hamp, according to whom the toponym "Prishtina" comes from the early Indo-European word "pri" meaning "fall" and the other Indo-European word "setin" meaning "stone" (in English the word "stone" is similar to ”setin"). Stonefall or fall of stones may be the meaning of the original toponym "Prisetina".

The first known mention of Prishtina in a written document dates back to October 1325. It was first published in 1913, by Lajos Thallóczy, Konstantin Jireček and Milan Šufflay, in the document work, "Acta et diplomata res Albaniae mediae aetatis illustrantia", as document numbered 710, in the first volume of this monumental work. It is about a letter in which Stefan Uroshi III (1276-1331), King of Serbia, also known as Stefan Decanski, writes to the Republic of Ragusa. In this letter, Stefan Uroshi III requests that if Elia and Thomas come from Ragusa, they bring the tribute or tribute of Saint Dhimtri to Prishtina (Pristinae). 3 At this time, Prishtina was the seat of Stefan Decanski. This shows that it already had some kind of importance as a place. From this it can be concluded that the time of the foundation of Pristina should be dated somewhere in the middle of the XIII century.

The second (important) early mention of Prishtina in a written source is the authorship of the Byzantine emperor John VI Kantakuzen (1292–1393), who, describing his meeting with the Serbian king Stefan Dushani, in 1342, writes that they met " ...there in an unwalled village called Pristinon". The two early documents written about Prishtina turn out to have as characters two Serbian kings, Stefan Dečanski and Stefan Dušani, because during the first half and middle of the XIV century, Prishtina was one of the seats of the Serbian kings, as it seems, at least as a summer vacation residence.

After the death of Stefan Dushan in 1355, his kingdom was engulfed in anarchy and it crumbled among his followers into many domains. About ten years later, sometime after 1365, Prishtina became the seat of Vukashin Mernjacevic, a Serbian prince who, precisely from 1365 until he died in 1371, reigned under the name Stefan Uroshi V, King of the Serbs and Greeks. In fact, he was killed on September 26, 1371 at the Battle of Marica, fighting against the Ottoman Turks, who had just appeared in the Balkans and who would overrun half of the peninsula with their armies in the following century. After the death of Vukashin, his possessions remained under the rule of his four sons, but according to the 16th century Ragusan chronicler, Mavro Orbini, the author of the famous work "The Kingdom of the Slavs", after the death of Vukashin, the Serbian ruler Lazar Hrebeljanović e conquered Prishtina and Novobërda.

Shortly after, Prishtina ended up as a possession of Vuk Branković, a Serbian nobleman who on January 20, 1387, in Prishtina, issued a charter with which he made an agreement with Ragusa for the regulation of trade relations with his possessions, including Prishtina itself. Here begins a period of about six decades during which Prishtina was home to a colony of Ragusa, merchants from the Republic of Ragusa in Dalmatia, which had become independent a short time before, in 1358. This is also the reason why the early history of the first two centuries of Prishtina, it is mostly evidenced by the documentary sources from Ragusa preserved in the State Archives of Dubrovnik and so much traced by historians.5

Precisely from documentary sources from Ragusa, life in Prishtina of the end of the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century can be reconstructed to some extent. In a will drawn up by the Ragusan citizen Matco de Suezda - the Latinized name of Marko Zvizdiqi - dated November 9, 1387, he left five ducats to finance the completion of the works of the Church of Saint Mary in Pristina, a Roman church.6

At the end of the XIV century, the Ottoman Turks increased their conquering expeditions in the Balkan territories. In the early summer of 1389, Prishtina witnessed one of the most famous medieval battles in the history of the Balkan peoples. About ten kilometers north of Pristina, in a wide field, an Ottoman army supported by a Serbian army and an allied army consisting of Serbs, Arabs, Bosniaks, Hungarians, Wallachians and Franks met between them. Well-known as the Battle of Kosovo since it took place in the Field of Kosovo, it took place on June 15, 1389. In the series of battles between the Balkans and the Ottomans, in the century-long period of Ottoman penetration in the peninsula, the Battle of Kosovo is the most well-known, not for its real importance but for the Balkan folklore and the religious and ideological myths that the Serbs created about it in the 19th century. This is the only battle in the six-century history of the Ottoman Empire, where a sultan was killed. During this battle, a local noble managed to summon Sultan Murat I Hydavendigar.7 Seven years after the Battle of Kosovo at the beginning of 1396, Ottoman troops attacked the lands that were under Vuk Branković's possessions and occupied Pristina as well. But being a city whose importance came from its customs, where goods and especially metals circulated, Pristina retained its cosmopolitan character and was not immediately Ottomanized. It will take half a century for Prishtina to enter the path of Ottomanization that turned it into a typical Ottoman center for the time.

From the documentary data of the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century, it is understood that Pristina had a very diverse population, especially because of the merchants settled there who had come from Ragusa, Split, Zara, Kotor, Tivar, Drishti and Ulcinj. . All these cities belonged to the eastern coast of the Adriatic, a Catholic area that contrasted with the Orthodox hinterland of the central Balkans where Pristina was located. The placement of these residents in the city explains the evidence for two Catholic churches in Pristina: the Church of St. Mary and the Church of St. Peter.8 A collection of wills dating from 1429 to 1442, left by different donors, provide clues for the clergy of these two Catholic churches in Pristina, in the last decades before the complete Ottoman occupation of the city.

In the 15th and 16th century

Sometime in early 1409, a Hungarian army during an attack in the surrounding area, attacked and burned Pristina. This is known from a letter in which the Ragusans of Pristina complained to Sigismund of Luxembourg, who since 1387 had received the crown of the King of Hungary. Throughout the first half of the 15th century, a dense commercial activity of merchants from Ragusa resulted in Pristina. From the books of the Ragusan Small Council, there are statistical data for the colony of Ragusans in Pristina, which range from 39 Ragusans in 1414, to 208 Ragusan citizens in 1437. But the Ottoman incursions at this very time brought many rivalries and conflicts between the Ragusans and the Ottomans, due to the conflicts of their economic interests. 9

In the fall of 1448, between October 17 and 20, Prishtina witnessed a fierce battle that took place between Hungarian and Ottoman troops in the Kosovo Field. Known as the Second Battle of Kosovo, this three-day battle marked the climax of the Hungarians' revenge against the Ottomans. At the end of this battle, the Ottomans, commanded by Sultan Murad II, defeated the Hungarians and their Vlach, German and Bohemian allies led by Janos Huniadi.10

This battle won by the Ottomans paved the way for the further advance of the Ottomans towards the central and western Balkans and their consolidation in these parts. It is not known exactly when Prishtina fell to the Ottomans, but it seems that by the time the Hungarians and the Ottomans met on the Kosovo Field in 1448, Pristina had already been taken by the Ottomans for a decade because it was owned by Skender Turku, while it results under the Ottomans for the first time since 1439, when the lord of Pristina was Isa Bey.11 At this time, the penetration and strengthening of the Ottomans was seen with attention and concern in Ragusa, which had great economic interests connected to Pristina, for because of the Ragusan colony in the city. In a letter dated June 12, 1430, written as a response to the Ragusan ambassador to Sandal i Bosnja on his announcement of the arrival of the Sanjakbey of Skopje in Pristina, the Ragusa authorities judged: "We do not believe in the possibility of an attack by Isaac that Sandali was talking about. This is not the reason for which this Turk comes to Pristina, it is more likely that he helps the Ragusans, since the Turks are at peace with Sigismund."12

So in the middle of the 15th century, Prishtina, once a merchant station city, took the form of an Ottoman kasaba city, when Sultan Mehmet II, who gained wide fame after conquering Constantinople on May 29, 1453, built a complex of buildings in Pristina in 1455. including a mosque, a hammam and a madrasa.13 From here we can talk about Ottoman Pristina and the Ottomanization of Pristina, as a process of acculturation that is most easily traced through the Islamization of its population.

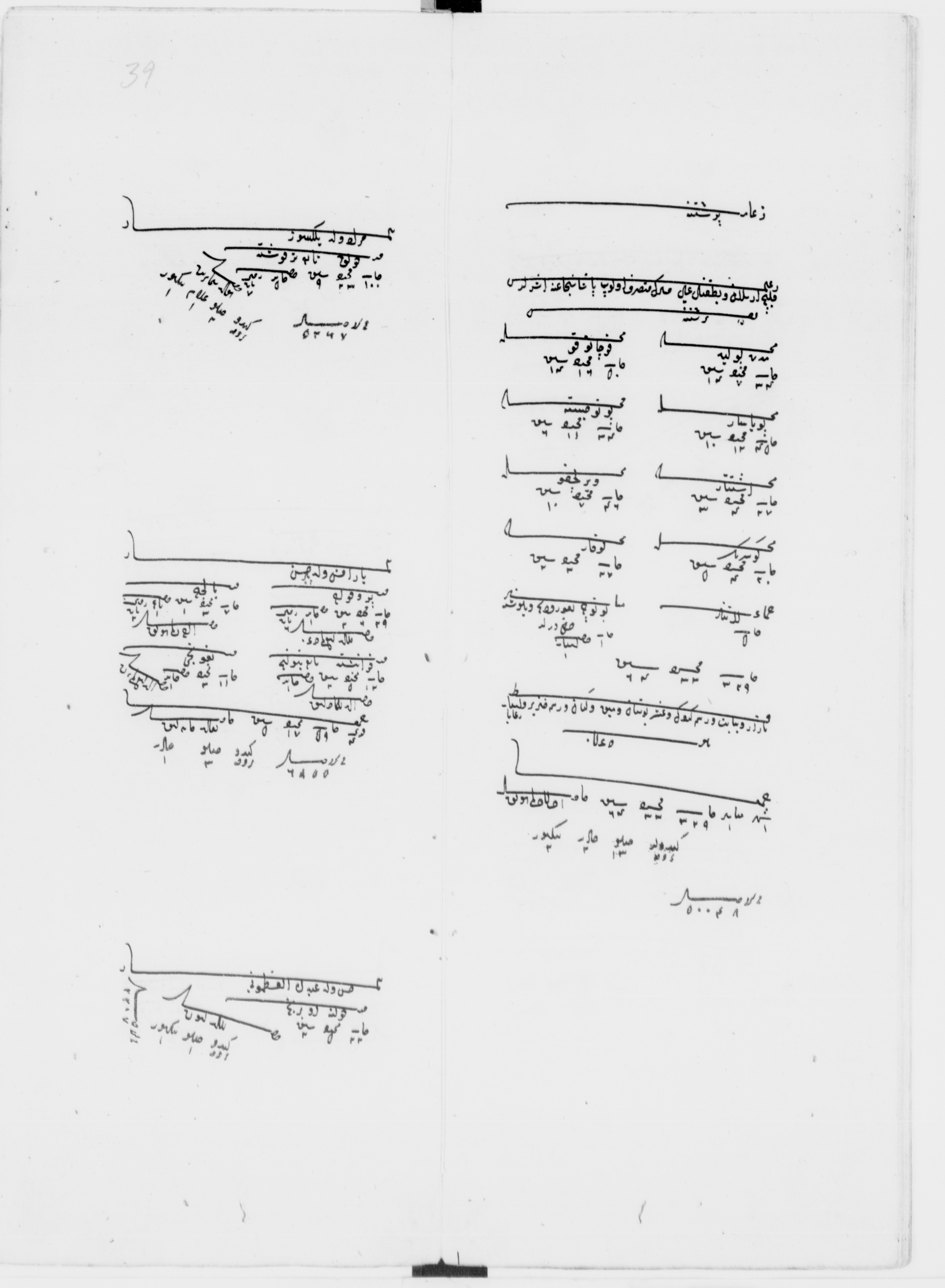

In an Ottoman register from 1477, when the Ottoman rule was consolidated in the city, Prishtina turns out to have 9 neighborhoods with a total of 351 houses, in this order: Mitropolit neighborhood with 48 houses; Kaqanovic with 64 houses; Pojasar with 55 houses; Potocishte with 40 houses; Merchant with 30 houses; Vërlićko with 56 houses; Kosiriq with 25 houses; Llukar with 28 houses and Latin with 5 houses. In another Ottoman register of the summarized type ("ijmal"), but after ten years, i.e. from 1487, Pristina has 51 more houses, these with Muslim residents.14

By comparing the data of the Ottoman notebooks, a relatively rapid progress of the Islamization of the population of Pristina within a period of a century is ascertained. According to a register of the Sanjak of Vučiterna, which was drawn up during the reign of Sultan Selim II, i.e. between the years 1566 - 1574, out of a total of 19 neighborhoods, Prishtina had 11 Muslim and 8 Christian neighborhoods. The neighborhoods with Muslim population were: the "Sultan Mehmed Han Gazi" mosque neighborhood with 46 houses; of the mosque "Mehmed Bey" with 29 houses; of the mosque "Sinan Bey Jaralu" with 24 houses; of Çarşia mosque with 11 houses; of the mosque "Hasan Bey" with 32 houses; "Emred Allaudin" neighborhood with 49 houses; of the "Jonuz Kadi" mosque with 34 houses; of the mosque "Jusuf Çelebi" with 38 houses; "Mir Hasan" neighborhood with 15 houses; of the "Hatunije" mosque with 11 houses and the "Ramadan Çaush" neighborhood with 20 houses. Meanwhile, the 8 neighborhoods with Christian residents were: "Moqalović" neighborhood with 63 houses; "Bathishte" neighborhood with 29 houses; "Xehriq" with 12 houses; "Bojsar" with 33 houses; "Latin" with 6 houses; "Shtitar" with 34 houses and the neighborhood "Llukar" with 27 houses. By simple calculation, it turns out that Prishtina in the middle of the 16th century had 309 houses with Muslim inhabitants and 212 houses with Christian inhabitants. Historian Muhamet Tërrnava, who has extensively studied these notebooks, claims that although they also contain the names of Prishtina's family heads, these anthroponomic data cannot be interpreted for researching the ethnic structure of the city's population. However, what is known for sure is that the majority of Prishtina's residents were Albanians and Serbs, and they are part of both religious communities of the city, i.e. Christians and Muslims.15

From the Ottoman registers of this time, also studied by the historian Skender Rizaj, a picture can be created for the economic life of the city of Pristina, since the Ottoman registers have also recorded the professions and activities of the heads of families. The following professions and trades are repeated there the most: shah, imam, muezzin, dervish, hatib, scholar, kadi, goldsmiths, hammamji, grocer, chatib, saraç, soapmaker, tabak, locksmith, nallban, merchant, hallach, tellall, barber , blacksmiths, horsemen and tailors. From the detailed ledger of the Sanjak of Vucitarrna from the year 977 Hijri, which corresponds to the year 1569/'70, it results that Pristina had an annual income from taxes of 94781 akçe. From the professions and trades recorded, it is understood that Prishtina had a lively Muslim religious life with many clergymen as well as a diverse economic activity of different trades such as leather workers, horse shoemakers, shoemakers, tailors, soap makers, ore processors and traders.16

In the 17th and 18th century

In the intervening two centuries of Ottoman rule, the kasaba of Prishtina took the form of a typical town (shehir) of the Ottoman period. Almost all the data of this period about the city mention Prishtina as a city connected with mining trade as well as a center located between important roads. The Turkish geographer and historian Haxhi Kalif Mustafai described Prishtina in 1648 as a medium-sized city, in a relief position surrounded by banks and where the supervisor of mines resided.17

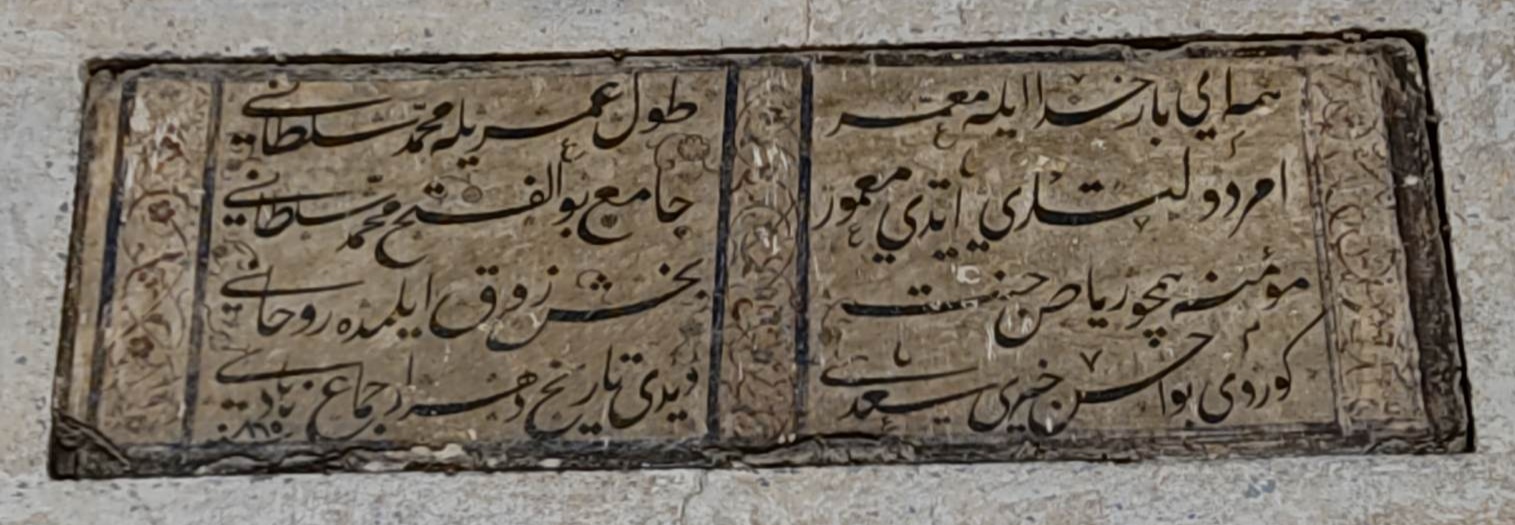

In 1660, the well-known Turkish writer Dervish Mehmed Zili, better known as Evlia Çelebiu, also stopped in Prishtina while accompanying Meleq Ahmed Pasha, the Governor of Rumelia, on his way from Bosnia to Sofia. In his well-known travelogue "Book of Travels" ("Sejahatname"), Çelebiu has dedicated about two pages of text to Prishtina, with some information about it as he found the city in 1660. In them, he writes that Prishtina had 2,060 one- and two-story houses, surrounded by walls and tiled roofs, with large yards and vineyards and gardens. Among them, he highlights the Saraj, i.e. the palace of Koxha Bodur Allajbeu and the court building. He claims to have counted a total of 12 shrines, of which 6 are mosques, one in the bazaar and others as neighborhood mosques. According to Çelebi, next to them in the city there were also madrassas, hadith schools, primary schools and dervish teqes. While among public architectural works, he mentions some public taps or fountains. In all of Prishtina, he did not find any buildings with lead roof, which for the time meant something grander and more luxurious, but he recorded a total of 11 inns in the city, from which he copied a chronogram, namely an epigraph from Hani i Haxhi Beu, with this textual content: “We are proud to say the date in words: This inn was built in 1032”. Converting this date from the Hijri calendar to the Gregorian one, it turns out that Haxhi Bey’s inn was built in 1623, i.e. 37 years before Celebi visited it and the city. During his trip to Prishtina, Çelebi counted 300 shops, in which he writes that you can find whatever you want, but which he claims are insufficient for the size of the city. He writes that these shops were organized in a market, but that the city did not have a bezistan, that is, a market covered and surrounded by walls. The Turkish writer praises the inhabitants of Prishtina as hospitable people, while the boys and girls of the city were known throughout the Ottoman territories for their beauty, which he attributes to the good climate.18

At the end of the 17th century, Prishtina became the headquarters of the Austrian Christian troops, during the Austro-Ottoman war of 1689. On this occasion, their commander General Picolomini placed his headquarters in Prishtina, where he met with the Bishop of Shkup, Pjeter Bogdani, who sent local troops with about 20,000 insurgents, all Christians. Unable to defeat the Austrian troops, the Ottomans also engaged Tatar mercenary troops, who by throwing infested animal corpses spread the plague as a biological weapon against the Austrians and the insurgents. Precisely infected by the plague, Pjetër Bogdani died in Prishtina on December 6, 1689. He was buried in the courtyard of the mosque of Sultan Mehmed II, which in those days had meanwhile turned into a Catholic church. But during days the Habsburg luck went downhill and the Austrian troops commanded by Holstein and Colonel Strasser left Prishtina one after the other in such a hurry that they left behind many ammunition and food reserves as well as some artillery pieces. In the first days of January 1703, Tatar and Ottoman troops entered Prishtina and took revenge on the few remaining inhabitants and on the city. According to the Catholic priest Gjergj Bogdani, Pjeter Bogdani’s nephew, they exhumed the latter’s corpse and threw it to the dogs in the center of the city of Prishtina.19 The pestilence of the mortar as an epidemic returned to Prishtina at least two more times: in 1703 and in 1737, the mortar spread in the city wreaking havoc on the inhabitants of the city and its surroundings.20