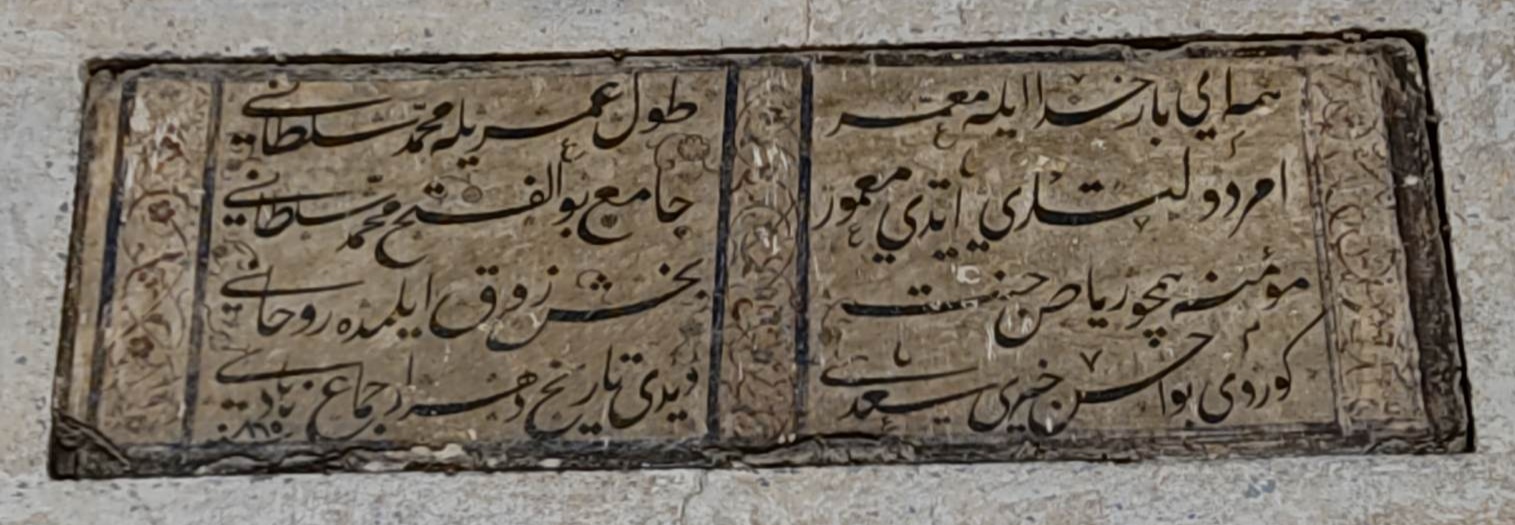

The holding of the Albanian cities under the Ottoman administration was manifested by great changes in the social-economic and political life, which was also reflected in the confessional structure of the city, which was a determinant of the changes in the urban landscape of these cities.1 Thus, along with the conversion of the inhabitants of Prishtina to the Islamic faith, the city was enriched with oriental-Ottoman style objects. Consequently, since the second half of the 15th century, Prishtina took on the appearance of a city with Ottoman urbanism, where the symbol of the nahija were the two main mosques built from the revenue fund of Sultan Mehmet II (1451–1481).2 We are talking about the Mosque of Sultan Murat, known as the Çarshi Mosque, or the Stone Mosque, the foundations of which were laid in the year when the First Battle of Kosovo took place (1389), while the works were completed during the time of Sultan Mehmet Fatihu, the annexer of Kosovo. The latter also built a mosque in his name, which in official Ottoman documentation is known as the Mosque of Sultan Mehmet Fatihu, while the local population calls it by several different names: the Mosque of Sultan Mehmet, the Mosque of Fatihu, the Great Mosque, and the Mosque of the King. According to the inscription (portal), the construction of this mosque was completed in 1460-1461.3

Depending on the increase in the number of residents of the Islamic faith in the city, the number of masjids (shrines for daily prayers) and mosques also increased. Therefore, in addition to the two main mosques mentioned, until the first half of the 16th century, some masjids were built that served for daily prayers. According to the rules of Islamic jurisprudence, in these small shrines the Friday prayer could not be performed, since there was no pulpit, something only allowed to be placed with the permission of the Sultan. Later, with the increase in the number of believers (after 1570), these shrines were raised to the status of mosques. For example The Mosque of Ramazan Çaushi, Jusuf Çelebi, Hatunije (of the Lady), Hasan Beg, Mehmet Bey, Emir Alaaddin, Jaralla Çeribashi and Hasan Emin, until 1569-1570, were all masjids.4* Meanwhile, the masjid of the Prishtina bazaar, which is evidenced in the Ottoman documentation of 1544, like all the masjids erected by the guilds in the Ottoman cities, had preserved this statute until 1930, when it ceased to function as such. Another mosque built between the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century is that of Pir Nazër, which is located on Haxhi Zeka street.5 At the same time, according to Stefan Gaspari's report from 1671, part of the urban fabric of Prishtina was the church of Saint Mary, whose roof was in ruins at the time.6

The Ottoman documentation also reveals two other classic Ottoman-style mosques, which were part of the urban center of Pristina and which do not exist today. One of them is that of Yunus Efendi, also known as the Llukaqi Mosque, which was built after half of the 16th century.7 The traces of which were revealed during the works of the Ibrahim Rugova square in 2012. This mosque, demolished in 1953 by order of the municipal assembly of Prishtina, was located in the place where the Swiss Diamond hotel is located today. The other mosque that appears in the Ottoman documentation of the 18th century is that of Halil Aga, for which we do not know either the location, the time of construction, or the time of destruction.8

Photo of Yunus Efendi Mosque (LLukaq), Source: Kosovo State Archives Agency (F857–10).

Photo of Yunus Efendi Mosque (LLukaq), Source: Kosovo State Archives Agency (F857–10).

Hammams (public baths) were part of the Ottoman urban structure as well, which developed during the Ottoman rule in the territory of Kosovo. Thus, during the first two centuries, more than 15 hammams were built in the space of today's Kosovo, which were at the service of residents and foreigners (workers, travelers, etc.) and as such served as public health facilities.

Unlike the city of Vushtrri, which was known for its public bath (term), since the time of Roman rule,9 the donor of the first hammam in Prishtina was Sultan Mehmet Fatihu, who in addition to the mosque (1460/61) erected the hammam, madrasa, mejtepe, library and inn (inn),10 all of them making up the classical complex (kylije) of the Ottoman city, which also included open and closed bazaars. Prishtina had a second hamam, known as the Old Hamam, and the ruins of this bath have been found near the building of the Parliament of the Republic of Kosovo.11 This finding is confirmed by the official records of the 18th century, which refer to the activity of it as a state hammam, as stated in the document.12 At the same time, according to the data of Koxha Sinan Pasha's vakuf, legalized in 1566, this second hammam was built in Prishtina, with a donation from Sinan Pasha Topojani, nicknamed Koxha.13

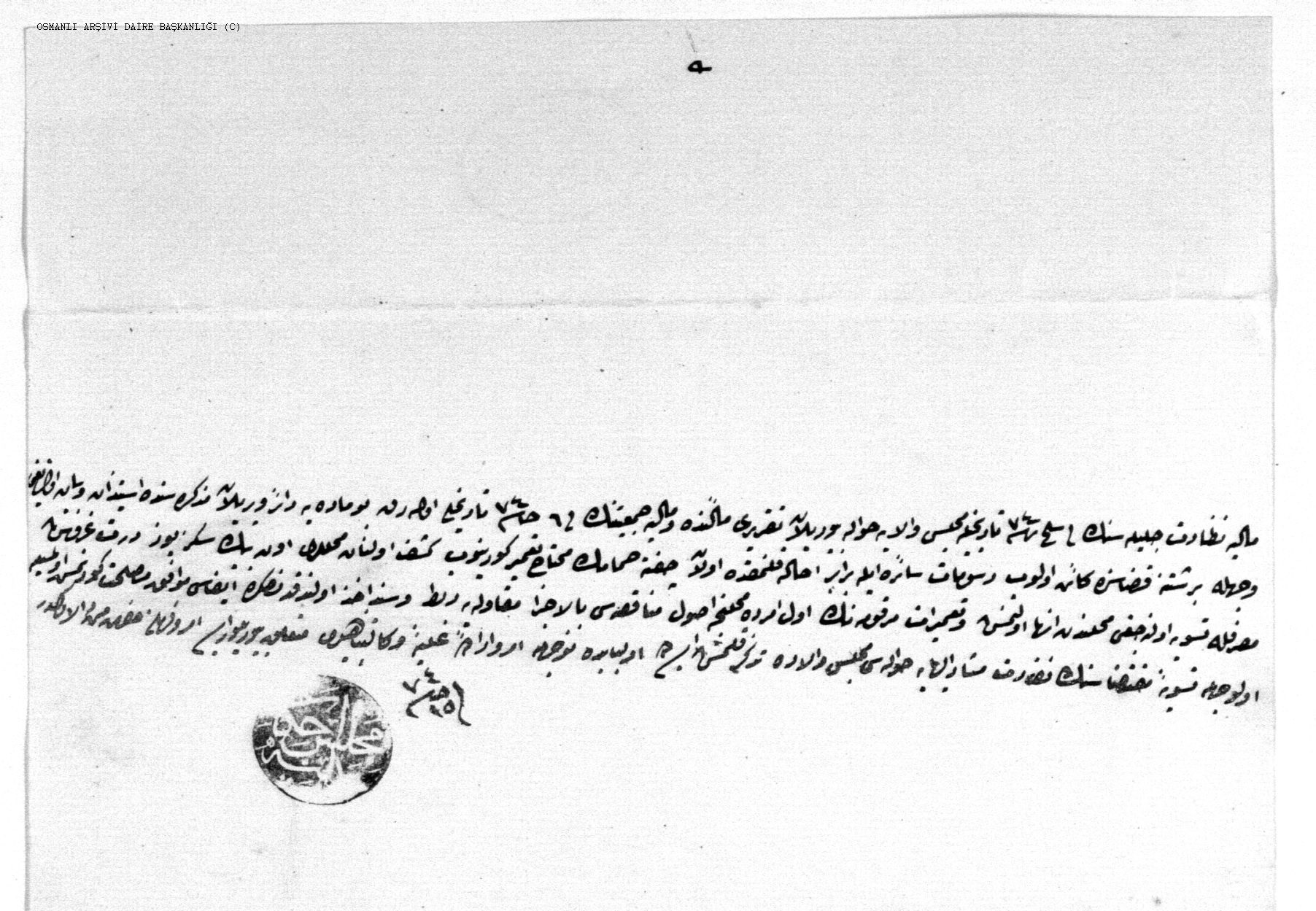

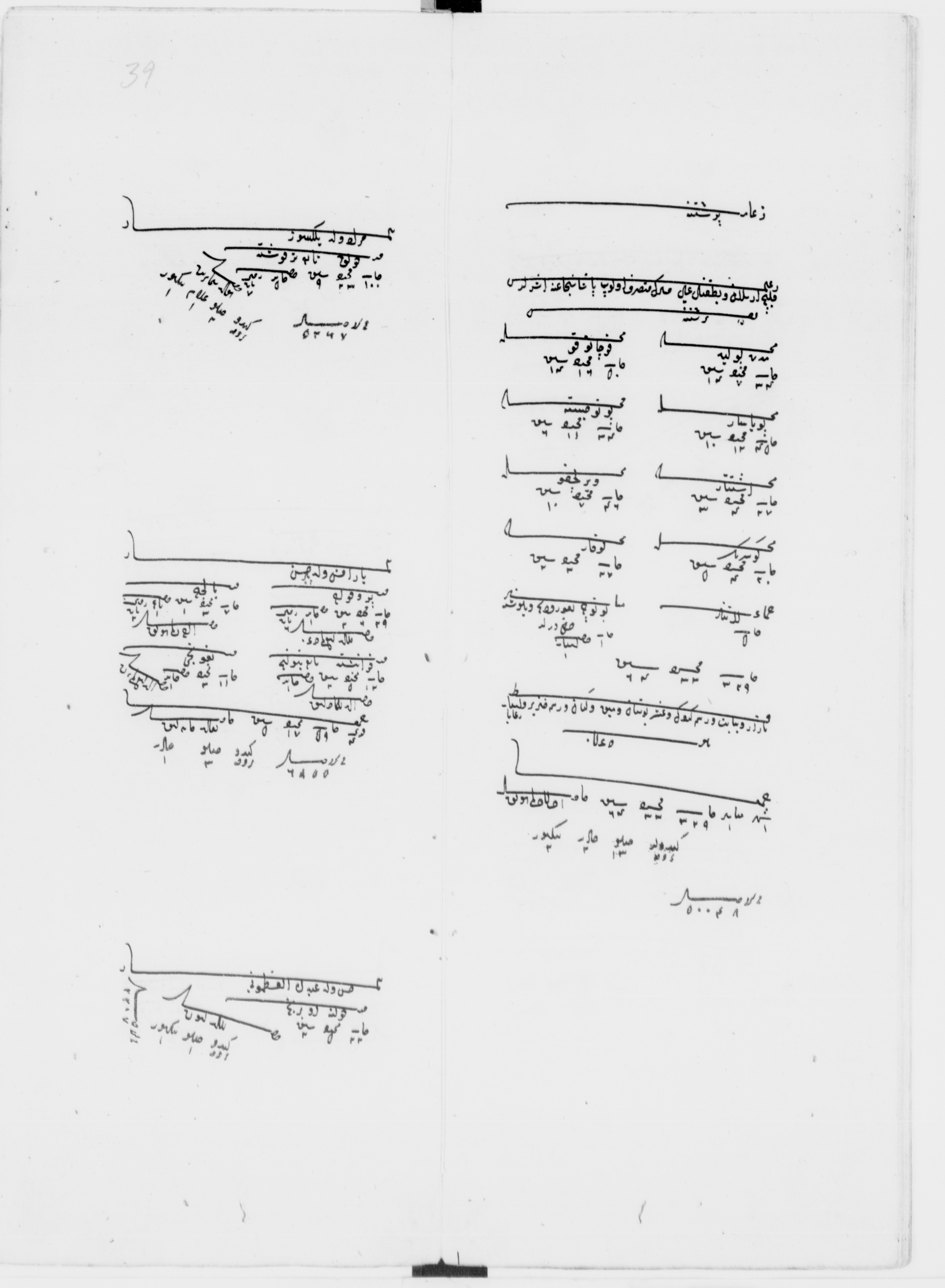

In the framework of the official Ottoman data, it can be seen that, due to the age of the Hammam building built by Sultan Mehmet Fatihu, renovations were made from time to time. For example, the following document, issued by the administration of the kaza of Pristina, dated January 2, 1858, displays the bad condition of the hammam facilities with two entrances (one for women and one for men),14 as well as the need for an investment of 10,804 groschi for its renovation and maintenance.15

At the time of the Tanzimat reforms, the urban development of the city of Pristina was even more rapid. Thus, as early as the first decades of the 19th century, it was enriched with the Mosque of Jashar Pasha (1834/35),16 known as the Middle Mosque; then the Kaderije Mosque (1893), which was built in the neighborhood of the Muhaxhirs;17 the tomb of Danjali; and the shrine of Sheh Mehmet Sezai. It was during this time, tha several importan architectural projects influenced by European styles took place, as is the cas of the government residence (assembly) (today the Museum of Kosovo), the clock tower, the high school, etc.19

The data of the annual report (salname) of Prizren from the year 1291 (1875) reveal a good part of the panorama of the city of Prishtina, which at that time, together with Gjilan, Kurshumli, Vushtrri and Prizren, were dependent kazas of Vilayet of Prizren. According to these data, in Prishtina there were 17 masjids and mosques, a teqe, a madrasa, a church, a synagogue, a clock tower, 14 inns (inns), 6 mejhanes (cafes), 525 shops, 1 closed bazaar (bedesten ) with 28 shops and 3 hammams.20 The same data is confirmed in the year 1318 (1900) of the Vilayet of Kosovo, where it is stated: "In Prishtina there are 500 shops, 20 hotels, 10 guesthouses, 1 clock tower, the building of the municipal assembly, 30 cafes, 2 couples' hammams and 1 other male-only hammam, 1 hospital, 1 weapons depot, barracks for army horses and a municipality office.21 Also mentioned is a flour factory near Prishtina, which is owned by the Mufti, Mustafa Hamdi Efendi and Murat Begut.

The aspect of road and telegraphic communication was also an important development for Prishtina as the capital of the Vilayet. The yearbook of 1896 refers to the railway line between Prishtina and Skopje. A rail line to which other cities in Kosovo had access. While the telegraph network stretched from Prishtina to Gjilan, Prizren, Vushtrri and Skopje. A special line of communication with Vienna, the capital of Austria, was also active.22

-

1

Ferit Duka, "Aspects of Urbanism and Architecture of the City of Berat during the XVI-XVIII", Ottoman Centuries in the Albanian Space (studies and documents), Tirana: UET Press, 2009, pg. 334.

-

2

Mosque of Sultan Murat (the market) and Mosque of Sultan Mehmet Fatihu (the Great).

-

3

Portal text: O Lord of the Universe, make (this Mosque) stand long.

During the whole life of humanity which Sultan Mehmed

He built and raised this building.

The mosque of Sultan Mehmed, the father of the conquerors (triumphs)(mosque) For believers (it is) like a garden of paradise (Paradise).

(that) grants them (believers) the best taste in the soul. When Sadiu saw this beautiful work He marked his (isospecific) date with the words "the gathering time of the ascetics" -

4

These official data on the status of Islamic shrines reflect the process of Islamization, which took off after the 70s of the 16th century, when the need was felt for the masjids to turn into mosques, so that the prayer (prayer) could be performed. ) of Juma (Friday).

-

5

For the history of the mosques and mosques of Pristina until the end of the XVIII century, see Agron Islami, "XVIII. Yüzyılda Kosovo: Socio-economic history", İstanbul Üniversitesi, İstanbul, 2021, p. 76-81; Agron Islami, Area of Kosovo in Ottoman times: a socio-economic history of the 18th century, Prishtina: Institute of History "Ali Hadri" - Pristina, 2024 (in press), p. 123-130.

-

6

Fermendzin, Eusebio (1892). Izprave hit 1579–1671. tičuće se Crne gore i stare Srbije. In Starine (25), Zagreb, p. 196–198. Original document: Tabular. s. Congregation. de propaganda fide. Origin. Vol. 220 fol. 69. (Translation: Yll Rugova)

-

7

Iljaz Rexha, "Sacral and profane monuments of the Ottoman period in Kosovo", ibid.

-

8

Agron Islami, Ibid.

-

9

For more, see Fejaz Drançolli, Destroyed monuments in Kosovo 1998/99, Prishtina: Institute for War Crimes Researches, 2015, p. 113-114.

-

10

Mehmet Z. Ibrahimgil-Neval Konuk, Kosova’da Osmanlı Mimari Eserler, Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 2006, p. 338.

-

11

Orges Drançolli, Domed Mosques in Kosovo, Prishtina: Institute of History "Ali Hadri", 2023, pg. 53.

-

12

Agron islami, ibid, 123.

-

13

Hasan Kaleshi, The oldest endowment documents in Arabic in Yugoslavia, Prishtina: Presidency of the Islamic Community of the Republic of Kosovo, 2012, p. 362.

-

14

Classic Ottoman hammams were divided into two equal parts with separate entrances. The entry for women was managed by a woman myteveli (administrator), while the entry for men was managed by a myteveli (administrator) burrë.

-

15

BOA. İMVL. (Copy from the Archives of Pristina, hereinafter KAP.) 387/16893, see also BOA. İ.ML. (CHAP.) 2/49; BOA. I. ML. (CHAP.) 20/15

-

16

Besir Neziri, "Vakëfnameja e Jashar Pasha Gjinolli", Islamic Education, no. 122, Pristina 2020, p. 77;

-

17

BOA. DH.MKT. (KAP.) 73/44 according to the document in question, "this mosque erected, immediately after the establishment of the Muhajir neighborhood, which is adjacent to the Hasan Bey neighborhood, in Pristina, as a sign of respect for the shehzade (prince) Abdylkadir Efendi, is named with his name, "Kaderije".

-

18

BOA. İ.HUS (KAP.). 73/144; ŞD.(KAP.) 1965/33.

-

19

Salnâme-i Vilâyet-i Prizren, Prizren, 1291, Prizren Matbaa-i Vilâyet, pg. 73-74.

-

20

KVS, 1318, Üsküp Matbaa-i Vilâyet, p. 560.

-

21

1896 (Hijri 1314) Kosova Salnamesi District, ibid. page 191.