In the 19th century, Prishtina reached its central position, from which it benefited and turned into the administrative center and later the capital of all of Kosovo. In the last century of Ottoman rule, the position and status of Pristina in the administrative divisions of the European territories of the Ottoman Empire changed many times. In the span of half a century, Pristina was most of the time a sanjak on its own, a few times a kaza and a time also a vilayet center, as can be followed according to the following sequence:

During the years 1846 - 1848, Pristina was the sanjak of the Eyalet of Skopje.

During the years 1849-1850, Pristina was the Sanjak of the Skopje Eyalet.

During the years 1851 - 1854, Pristina was the Sanjak of the Skopje Eyalet.

During the years 1855 - 1864, Pristina was the sanjak of the Eyalet of Skopje.

During 1865, Prishtina was the capital of Prizren, part of the elajet of Skopje.

During 1866, Prishtina was the sanjak of the Eyalet of Skopje.

During the years 1867-1868, Prishtina was the capital of Prizren, part of the ejalet of Skopje.

During 1869, Pristina was the capital of Prizren, part of the vilaye of Shkodra.

During the years 1870-1871, Pristina was part of the vilayet of Prizren.

During the year 1872, Prishtina was the sanjak of the vilayet of Kosovo.

During the years 1873-1874, Pristina, the kaza of Prizren, part of the vilayet of Prizren.

During the years 1875-1877, Prishtina was the capital of Prizren, part of the vilayet of Manastir.

During the year 1878, Pristina was the center of the province of Kosovo.

During 1880, Prishtina was the capital of Prizren, part of the province of Kosovo. During the years 1881-1912, Prishtina was the sanjak of the vilayet of Kosovo.1

In the summer of 1831, Pristina and Shtimja became the scene of a Bosnian uprising. When Sultan Mahmud II granted autonomy to Serbia and 6 areas of Elajet of Bosnia, the Bosniaks rebelled and revolted. Thousands of united Bosniaks elected Captain Husein Gradaščević as the commander of Bosnia, who at their head headed towards Kosovo to face Reshid Mehmed Pasha, the Grand Vizier who had set out to quell the Bosnian uprising. This Islamicized Georgian confidently came to Kosovo through Skopje, since only a year ago he had extinguished almost the entire Albanian pariah, massacring them in Manastir. In the summer of 1831, on his way to Kosovo, Husein Gradaščević took Peja, before leading about 52,000 Bosnian insurgents stationed in Pristina. Although with equal numbers, the Ottoman army was superior in armaments, so the Bosnians were tactical, sending forward Ali Pasha Fidashiq who attacked the Ottomans and retreated almost defeated. The battle was taking place in the surroundings of Shtime, on July 18, on a Monday. Believing that he had won, Reshid Pasha sheltered his artillery and cavalry in the forest from the heat, while Bosnian insurgents led by Gradaščević made a surprise attack and routed the Ottoman army. The Bosnian attack was so lightning fast that even Reshid Mehmed Pasha, the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire who had begun to be called "Albanian specialist" was injured. On August 10, Bosnian insurgents gathered in Pristina and proposed that Kapedan Husein Gradaščević be declared Vizier of Bosnia. At first he refused but then he accepted and this was made official on September 12 in an assembly in Sarajevo. In the history of Bosniaks, Kapedan Husein Gradaščević would be called the Dragon of Bosnia (Zmaj od Bosne), while in historiography his battle would also be known as the Bosnian Battle of Kosovo in 1831.2

During this time, Prishtina was the city where Bosnian insurgents and Albanian insurgents joined forces, as both sides were against the reforms initiated by the High Gate in Istanbul. But unlike the insurgent population, the governor of Pristina, Jashar Pasha, did not join the uprising, trusting the promise of the Ottoman government that he would not replace him with any foreign official. At the beginning of February 1832, the insurgents captured the derbend of Gjilan and threatened Jashar Pasha. They had joined the Bosnian insurgents, whose entry into Mitrovica alarmed Reshid Mehmed Pasha, who sent Mahmut Pasha Prizren to help Jashar Pasha of Prishtina. Despite several successful battles, the Bosnian and Albanian insurgents were finally defeated on June 4, 1832 in Pallama near Sarajevo. However, Prishtina was also in turmoil during 1833 and especially after May 1834, as the inhabitants of the surrounding villages from the provinces of Llapit and Gollaku revolted against the Ottoman tax collectors.3

Only four years later, in 1838, Pristina was visited by the Austrian geologist Ami Boue, who in his classic work on Turkological studies "European Turkey", describes Pristina as follows: "The only recognizable buildings of Pristina are a clock tower and twelve mosques, of which two are of a higher construction, round in shape, with arabesque paintings and sayings of the Koran. A small mosque was built by Jashar Pasha, who had been in this post in the years 1837 and 1838. The bazaar is covered with boards, a cafe is at the junction of the three main streets of the city. The Pasha's mansion is a partly wooden building, it has two wings and one floor with a large square courtyard, wide corridors and wooden stairs, as is the custom. One wing of the guest house is painted with arabesques, it communicates from above the street with the harem, also a rather large house as well as in the greater part of wood, closed for reasons of jealousy, the couch of the Pasha had no glass windows, the place the open windows were simply closed by large wooden shutters, also on the ceiling there were swallows' nests. Pristina appeared to us to have a population of 7,000 to 9,000, among whom are a large number of Orthodox Serbs together with Arnauts and semi-Muslim Serbs."4

Apparently, after the visit of Ami Boues in 1838, there were no such foreign visitors in Pristina for exactly twenty years, until on October 30, 1858, the German jurist and diplomat Johan Georg von Hahn arrived in the city. At least that's what the mother of the pasha of the city told him, in whose guest house he stayed for two nights. Johan von Hahni found Pristina full of soldiers, as according to him, this was the second place after Manastir where military exercises were mostly carried out in the western half of Rumelia. He describes Pristina as very connected with the inhabitants of the villages of the province of Llap and Gollaku, for whom he writes that they hold regular popular assemblies, for which he made this note: "Upper Gollaku includes 19 villages that hold the assemblies of them in the Prapashtica mosque. The 21 villages of Lower Gollaku gather near the village of Sfircë. The 20 villages around Pristina in turn gather in Orllan and the 22 villages of Podujeva gather in Podujevë."5

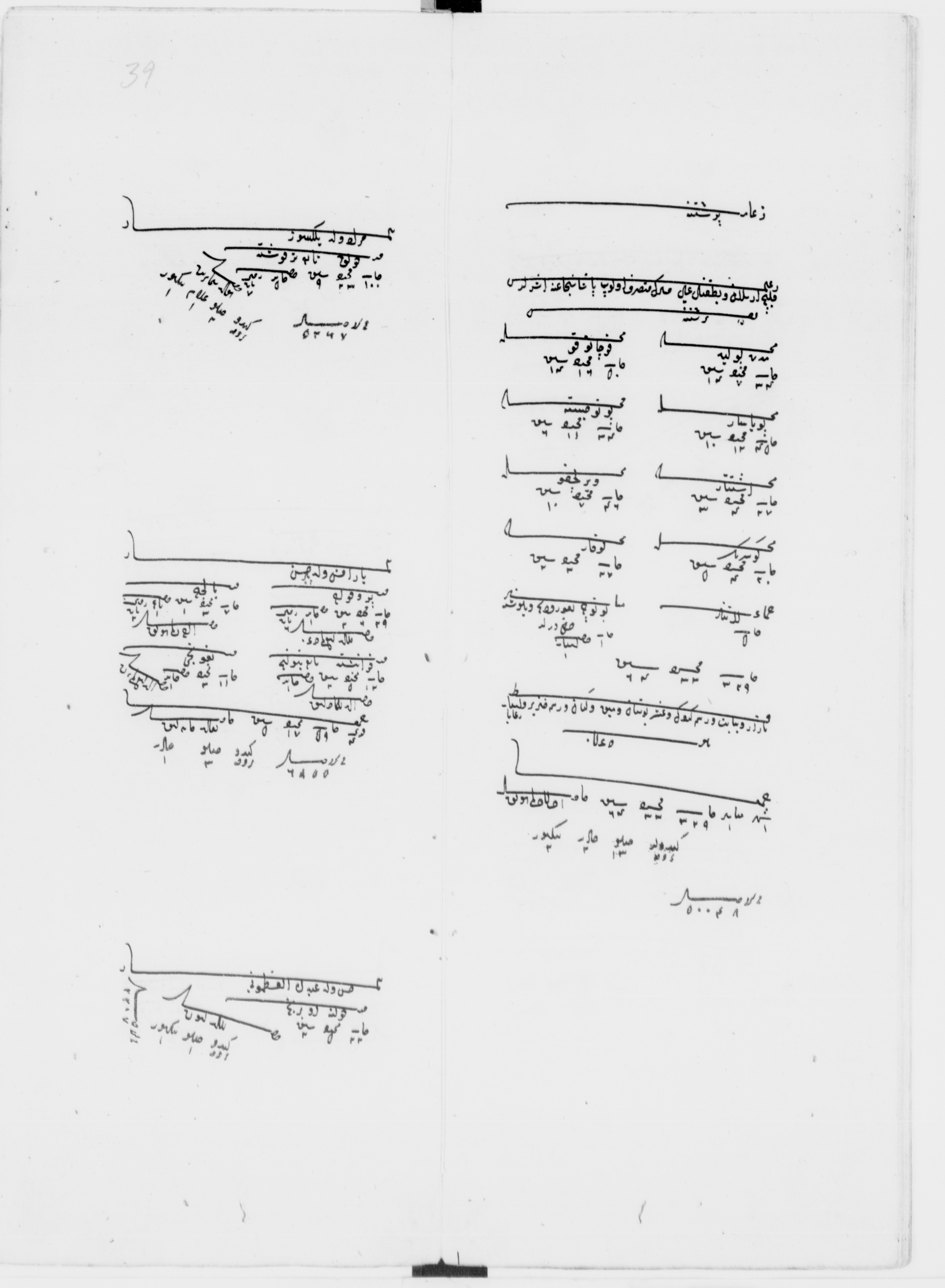

In a special register of lands, properties and income of the population, from the year 1844-1855 (1260-1261 h), 1066 houses with 7462 inhabitants were registered in Pristina. Of these, 4,900 residents or 65.66% were Muslim Albanians, 1,673 or 22.42% were Orthodox Serbs, 868 or 11.63% Roma and 21 Jewish residents.6 This statistical data conveys the ethnic panorama of Pristina as a city with an Albanian majority and a Serbian minority. and with a significant Roma community. Apparently, the 21 Jewish residents resulting from this register were the nucleus of a nascent Jewish community in Pristina, which in the second half of the 19th century grew to make up almost a sixth of the city's population. Within a period of half a century, the population of Pristina increased by two and a half times. In the Ottoman years of the early 1900s, Pristina turns out to have 22,236 inhabitants, living in 3,690 houses grouped in 12 neighborhoods. This was the total number of 18,223 Muslim residents, 1,786 Orthodox Christian residents, 1,922 Roma and 305 Jews.7

This data for the Jewish community of Pristina also coincides with the data published in 1904 by the "Bulletine de l'Alliance Israelite Universelle 1904", which records 300 Jews in Pristina. Those were the last years of the Ottoman rule in the Balkans and in 1911, when the Spanish researcher of Sephardic ballads Don Manuel Manrique de Lara visited Kosovo, he also recorded in Pristina a Castilian song that was sung by the Jews of Pristina: "Una pastora yo ami" . The first verse of this song said:

Una pastora yo ami

A shepherdess I once loved, Una hija hermosa, /

A beautiful maiden, De mi chiques yo la adore, /

In my childhood I adored her, Mas que ella non ami. /

And I didn't want anyone other than her.8

In 1877, when the vilayet of Kosovo was created, Prishtina became its capital and remained so until 1897, when by decision of the Ottoman government, the capital was moved to Skopje. This prompted protests in Pristina and protests by Pristina's mayor in Istanbul, but this decision was not reversed. It was at this time that the writer Branislav Nušić came to Pristina as the consul of Serbia, who in his work "Kosova: Description of the Country and Population" has built a panorama of the city describing Pristina as he found it when lived in it. "Even today Pristina is dominated by narrow and damaged roads, poor trade, etc., but, nevertheless, it is the most important place in Kosovo, or, in fact, the capital of Kosovo."9 He praises the hill of Drogodan for the vineyards and especially for the wide view of the relief it offers, while writing about the gathering of residents in the neighborhood, Nushiq writes: "Prishtina is mainly divided into four parts (quarts): Panairiana, Varoshi, Lokaqi and Ciganlia. In Panairiana and Lokaq live mixed Serbs, Turks and Albanians; in Varosh there are only Serbs, while in Ciganli there are Serbs and Roma. In addition to these quarters, the middle of the city includes Çarshia and since the arrival of the Emuhajirs, they have also created their own special neighborhood. Officially, Prishtina is divided into thirteen neighborhoods, regardless of the above division. These neighborhoods are: Jarari - the neighborhood of Ceribashi; Pirinasi, Alaedini, Hasan bey, Januz Efendiu, Hasan Emini, Ramadania, Hatunija, Mehmet bey, Jusuf Çelebiu, Xami Çebiri, Xami Segiri and Hamidia."10

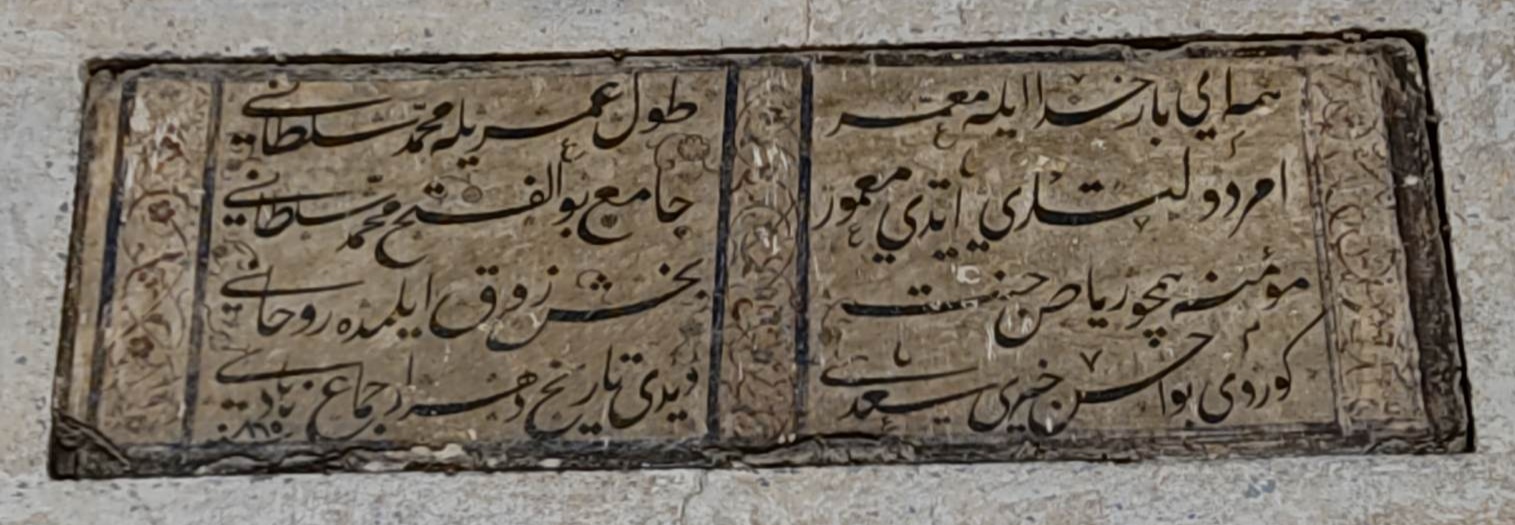

What Pristina looked like at this time, a more visual image can be created thanks to the photographs taken in Pristina since the end of the century. XIX onwards, and there are many. In these photographs, it can be seen that the city was concentrated in the area where the three most dominant mosques of Prishtina stand, that of Sultan Murad I in the city market, the mosque of Jashar Pasha near the Ottoman administration's residence and the mosque of Sultan Mehmet II, near the bazaar. In 1873, when the Ottoman government had built the railway line connecting Thessaloniki with Nis, Pristina had benefited as the center of one of the stations of this road, but in the first two decades of the 20th century, Pristina turned out to have remained a wrinkled city, with narrow roads and no modern infrastructure, backward and provincial. This can be easily seen in dozens of photographs of the city taken in the first three decades of the twentieth century.11

At the end of 1912, Pristina experienced a bloody tragedy when the First Balkan War broke out, as Montenegro, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece attacked one after the other the Ottoman Empire in its remaining territories in Europe, which were mainly dominated by Albanians. On the afternoon of October 22, 1912, Chetnik units led by Vojislav Tankosić entered Pristina and paved the way for the Third Army of the Kingdom of Serbia. Serbian military troops and Serbian Chetnik paramilitary groups entered the city of Pristina killing 5,000 men. in the villages of Pristina and in the city.14 This was also reported in an article of the end of that year in the newspaper "The New York Times" dated December 31, 1912, where it was written that 5,000 people were killed in the vicinity of Pristina, by Chetniks and Serbian soldiers who they killed the men in front of the women and slaughtered the children with bayonets.15

The First World War found Pristina and the entire province of Kosovo occupied by Serbia. After that, it remained as part of the Serbian-Croatian-Slovenian Kingdom or the Kingdom of Yugoslavia until the years of the Second World War. After the end of the Second World War, a period will reopen which will extend throughout the remaining decades of the 20th century, when Prishtina and the province of Kosovo as a whole will remain without the political will of its majority Albanian people under the communist regime and socialist of Tito's Yugoslavia and Milosevic's Yugoslavia in the last decade of that century. After a bloody war from late 1997 to mid-1999, on June 10, 1999, Prishtina would be liberated from Serbian military, paramilitary and police forces, when Kosovo Liberation Army troops and British NATO troops they entered the city. Nine years later, as the capital of Kosovo, Prishtina will become the true capital of a state, the youngest in Europe, the Republic of Kosovo.

-

1

Tahir Sezen, Administrative division of Albanian vilayets (Names of places and their status), trans., H. Ahmedi, Prishtina: Kosovo State Archives Agency, 2021, ff. 270-271.

-

2

Hamdija Kreševljaković, Husein kapetan Gradščević: Zmaj od Bosne, Sarajevo: Hrvatsko kulturno društvo Napredak, 1931, ff. 15-29.

-

3

Petrika Thengjilli, Anti-Ottoman Popular Uprisings in Albania 1833-1839, Tirana: Academy of Sciences of RPSSH - Institute of History, 1981, ff. 119-124.

-

4

Ami Boue, Albania in European Turkey, trans., I. Angoni, Tirana: Plejad, 2011, p. 142.

-

5

Johan Georg von Hahn, Reise von Belgrad nach Salonik, Vienna: Tendler, 1861, ff. 112-128.

-

6

Kristaq Prifti, Population of Kosovo 1831-1912, Tirana: Academy of Sciences of Albania, p. 269.

-

7

Kristaq Prifti, Population of Kosovo 1831-1912, Tirana: Academy of Sciences of Albania, p. 269.

-

8

Kristaq Prifti, Populsia, vep.cit., ff.599-600.

-

9

Durim Abdullahu, Kosovo and Israel: interchangeable state-buildings, Pristina: Koha, September 27, 2020, in https://www.koha.net/veshtrime/238942/kosova-dhe-izraeli-shtetndertime-te-nderkembyeshme

-

10

Branislav Nushiq, Kosovo: Description of the country and population, trans., Rrahim Sadiku, Prishtina: Zgjimi, 2015, p, 227.

-

11

Branislav Nushiq, Kosovo, p. 231.

-

12

Valbona Shujaku, Prishtina Poetic Memories, Prishtinë: Public, 2011.

-

13

Valbona Shujaku, Prishtina Poetic Memories, Prishtina: Public, 2011.

-

14

Tafil Boletini, Kujtime, Tirana: Klean, 2011, p. 135-138.

-

15

Leo Freundlich, Albaniens Golgatha: Anklageakten Gegen die Vernichter des Albanervolkes, Wien: Verlag der buch, 1913, p.9.

-

16

The New York Times, New York: 31 dhjetor 1912.