Some historians practice their craft by leaving aside the focus on rulers, politicians, and powerful men.1 And for good reason: the latter, although they make up a small percentage of the population, take up the majority historical narratives as we know them. Leaving in the dark the main categories of social life, artisans, soldiers, slaves, peasants, ordinary citizens, artists and other trades, etc. In this peripheral part of historiography, women take place as well.2 Having this in mind, we are publishing here some fragments that tell us a bit about the position of women in Prishtina in the 18th and 19th centuries, when the city was under Ottoman administration. The history of the city of Prishtina itself, in general, can be included among the neglected narratives; where that of women constitutes the marginal of the marginal. Therefore, the bits that we are bringing below are just a step towards opening new paths in making improvments in this direction.

Of interest are some instances from the 18th and 19th centuey. The fiest one comes from a recent article by Ageon Islami, published in the journal Kosova in 2020:3

"For the Albanian researcher, the truth about the accuracy of the Ottoman household registrations, the results of which were stored in the Tahrir notebook fund,4 and in addition to this, it also applied the recording of daily events, which were initially stored in the Myhimme notebooks, and later, respectively from the beginning of the century. XVII, depending on the topics, new funds are created.5 As a result of the variety of topics, today in the Ottoman archive we have various funds that contain data of interest for the social, economic and political history of the Ottoman subjects. An important fund for these topics is the complaints and demands of citizens/Ottoman citizens of the territory of Kosovo. [...]

A complaint [...], which highlighted the gender dimension, to which the answer was returned in 1764, was exercised by Asija from Pristina. She complained on behalf of her daughter, Bun. The latter, in 1756, was married to Mahmud from Prizren. After a short time due to difficult economic conditions, her husband returned Buni to her father's house in Pristina and in the presence of witnesses said: "In case I do not return within 20 days, let it be understood that Buni it is not under my crown". After Mahmudi had not returned to his wife, Bun's mother, after three years, namely in 1759, the court of Pristina provided a confirmation that Bun's ex-husband (Mahmudi) no longer had any rights. conjugal to his daughter and that there was no obstacle to betroth her to Abu Bekir Agana from Pristina. The latter, during the tying of the crown, had promised 350 kurush as a wedding gift (mehir), gold and various wedding clothes. However, Abu Bakir Agaja had also separated from Buni and had not fulfilled the promises given in the engagement. Asija had made her complaint to the highest level of justice in Istanbul, in which case she demanded that justice be done to her daughter's right, for the benefit of the wedding gift (mehr-i mueccel), the wedding clothes and the right to payment in cases of separation (iddat nafakasi). In response to Asija's complaint, it was said that, "... the accused (Abu Bekir Agaja A.I.), has not responded to the invitation of the court of Pristina, and two fatfas have been issued for this matter, through which the kadi of Pristina is ordered to find Abu Bekir and the latter to compensate the rights (the above-mentioned A.I.) to his ex-wife, Bun"6 . shariat in matters of justice in relation to women's rights in an Islamic state, such as the Ottoman Empire.

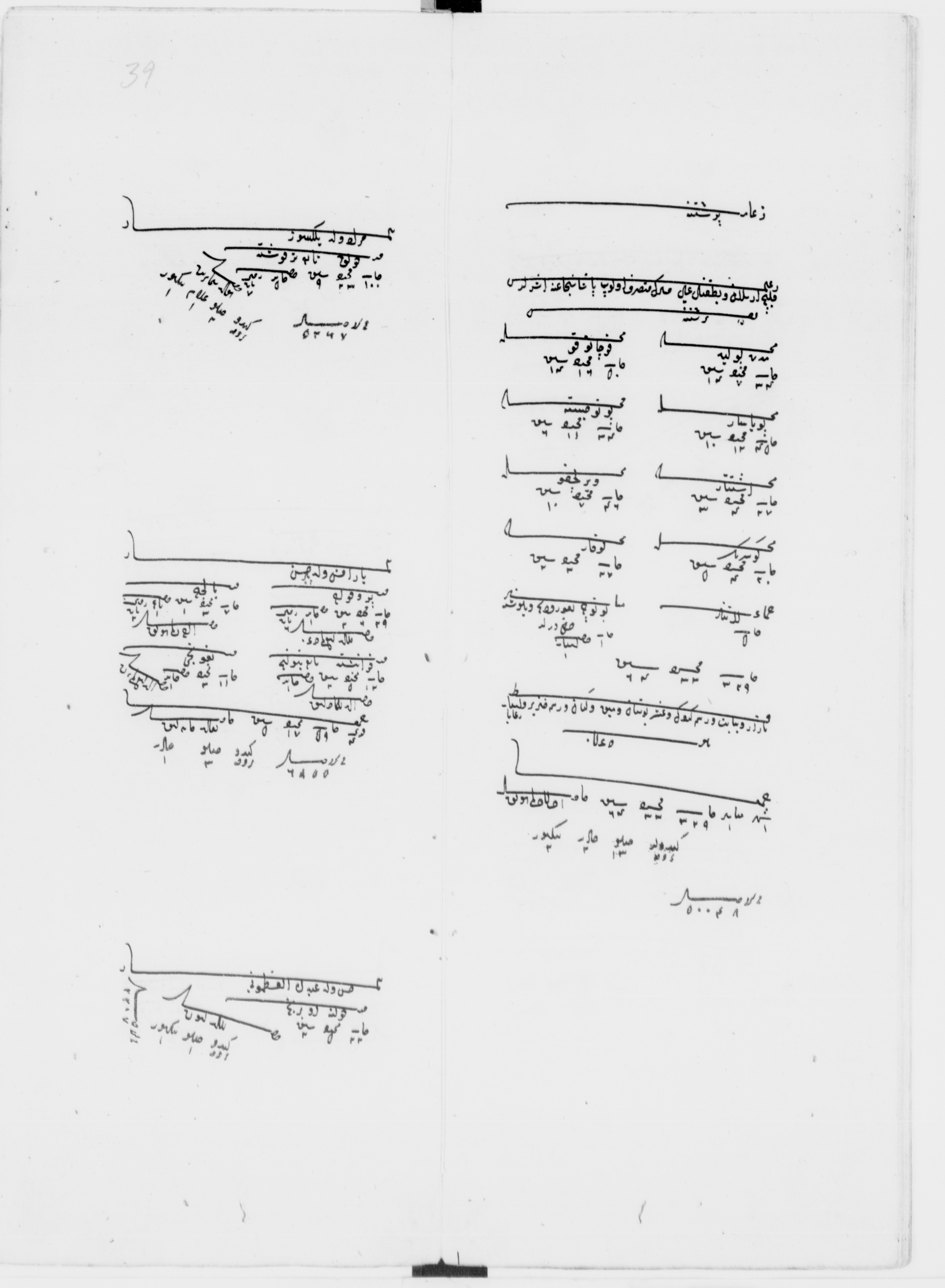

Another case is reflected very well in the letter that we are bringing below, which was also translated and found by Agron Islami. In this second case, which chronologically comes some 10 years before the first, on can clearly see that not only the issue of marriage was important for the women of the time, but the issue of property inheritance as well. Unfortunately, the final decision of the court seems to have been against the two sisters, causing them to lose a mill near Pristina. Full letter:

"Decision addressed to the Vali of Rumelia and the kadis of Vilçiterina: Dizdar of the castle (of Vushtrri), Ali, said that his great-grandfather, in the village of Obranç e Poshtme, which depends on the nahija of Llapi, had two mills, the borders of which they are known. However, as a result of the invasion of the infidels (Austrian armies), they have been destroyed and no one has taken care of their recovery. For 40 years in a row, they remained in that state and almost lost their tracks. At the same time, it was also refused [by the local bodies] to grant the work permit. Then, referring to the legal right, a permit was issued and they have been active for 9 years in a row. Until, [one day] the ladies, Hatixeja from Prishtina and Kaja from Yrgypi, came, claiming that, "your great-grandfather sold the mills to our great-grandfather, as early as 38 years ago. Thus, the legal right to use the mills belongs to us" and in the name of the law, also with the aim of hindering me, they took the matter to the court. But after listening to them, the judicial body of the valium rejected their claims, issuing a decision (bujuruldu). However, those mentioned have not withdrawn from their demands, begging for an interpretation from the Sheikhul-Islam body in Istanbul. On this occasion, a fatfa was also issued by Sheikhul-Islam, where it is established that the mentioned request has no support. This written decision of the bench should be applied without making any changes. March 1736. (See Documents)7

In the next century, the 19th, we encounter a contrast between two women visitors from Great Britain and the residents of Prishtina regarding the role of gender in the society. This is best observed from this fragment that comes from the book published in 1867 by two visitors Georgina Muir Mackenzie, Adelina Paulina Irby after visiting Prishtina as well. It should be noted that the guidebooks had their own prejudices against the Albanians, as is clear from this text:

"The school in Pristina contains a second large room, which would be suitable for a class of girls; but as usual there was a teacher missing and the customs of this part of the country were against boys and girls learning together. There was another obstacle. Even the boys on the streets here were harassed by the Albanian rioters (arnaout), - can you imagine what the fate of the girls would be like? This argument was singled out by Koxhabashi and then the school director replied: - "Do you know what they told me? The new Mudiri informed the majlis [municipal assembly] that it was the Sultan's pleasure that the children of his subjects go to school, without excluding the children of Albanians (arnaouts). Now if the young Albanians were locked in their duties [in schools], ours could walk the streets without worry." Koxhabashi glanced at us, as if to see how much we believed this, and then said briefly: "When the Arnaouts shut up and go to school like the rest, it will certainly be a great thing."

The aforementioned Koxhabashi was not particularly liberal regarding women's education. He emphasized to us that in their community many of the boys were still uneducated and it would not be good for the women to know how to read and write before the men. After that, we showed her some beautifully bound books and told her that the contents were stories and travelogues written by women. He examined the works closely and asked the schoolmaster, who knew Latin letters, to decipher the title, adding: "Are you absolutely sure that it is neither a letter nor a song?" "Very sure," we answered; and the school principal confirmed our statement. Then Koxhabashi said: "If women are going to write such books, we should see what ours can do."

After [Koxhabashi] left, the school director told us that the residents of Pristina generally have the gift of improvising poetry, and that to the national songs that they continuously recite, they add others composed for different events in their lives. Of course this gift also goes back to the intimacy between the sexes, and so there is a notion that if women could write, they would be writing love letters forever. Such ideas naturally prevail in a country long subjected to Mohammedan influence, but the old songs tell us of Serbian ladies who 'wrote like men.' (See Documents)

In Prishtina, as has been said elsewhere, religious schools have been known at least since 1575, where they taught in different languages such as Arabic and Persian. These schools, which operated continuously until the beginning of the 20th century, were only for boys. For the girls of the city, a school was opened for the first time in 1887.8 But a school for Serbian girls was apparently opened earlier.9

Instead of an end: a beginning

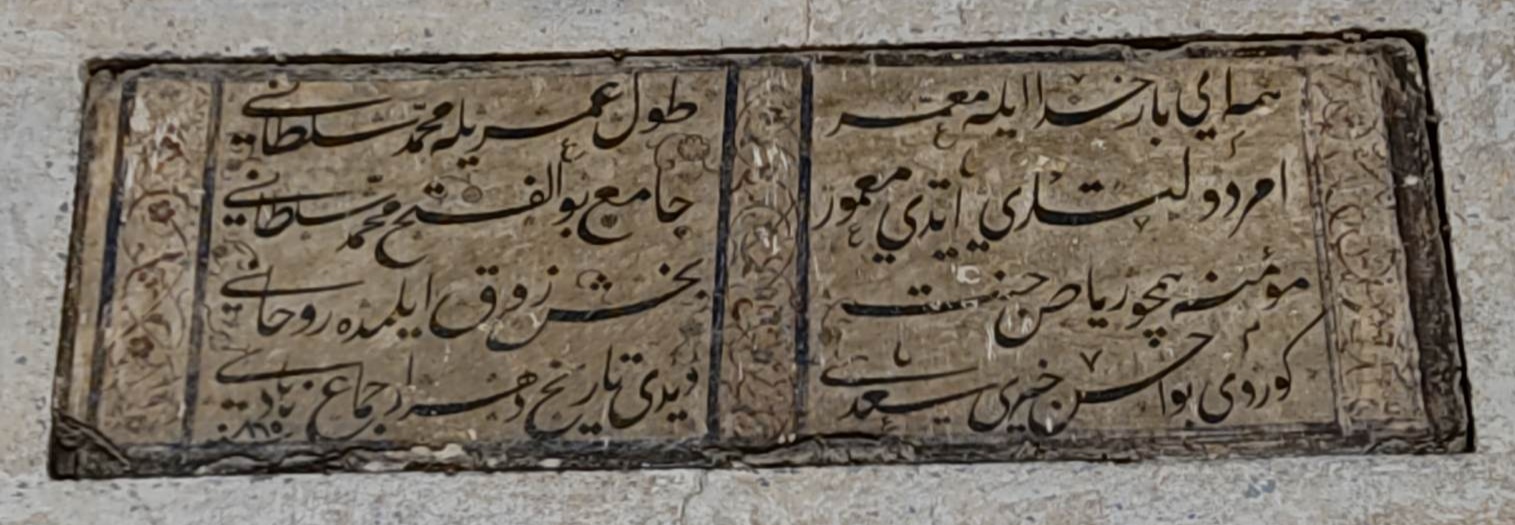

The three fragments that we presented above are just a small example of the history of women in Prishtina. It should be noted that at the end of the 14th century, Prishtina was practically ruled by a woman. She was Mara, of the family of the Serbian rulers Branković, and who continuously appears as a signatory of the documents of the time regarding the issues related to possessions in Prishtina and the surrounding area.10 Or, in the 16th century in Pristina, the shrine of Hatunija appears, woman's name (today a mosque near the city market).11 A few centuries later, in the 60s of the XIX century, we find in Pristina a factory for the production of soap (named Misk), all the workers there were women.12 The history of this plant is very little studied so far. The early history of Prishtina, the one before 1912, is untold in the drawers, in the many files of the courts, correspondence, endowments of the time that fortunately have been preserved until today in the archives (mainly in Istanbul). Other materials that may come from the archives in Venice, Rome and Vienna are also of interest, but in volume and detail they are mostly minor compared to the main ones that are Ottoman. The study of these documents to bring us a decentralized perspective of history is of fundamental importance.

-

1

A special thanks to prof. Eli Krasniqi for comments and suggestions during the writing of this article. The "social history" of the Annales school, the "decentring" of Nathalie Zemon Davis or the "microhistory" of the Italian school are some of the perspectives that illuminate social life throughout the past, but leaving aside the focus on rulers, politicians, and powerful men. On these three perspectives and their interconnection see Nathalie Zamon Davis (2011). Decentring history: Local stories and cultural crossings in a global world. In History and Theory (50), 188–202. For microhistory see also Carlo Ginzburg / John Tedeschi / Anne C. Tedeschi (1993). Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know about It. In Critical Inquiry, (20) 1, 10–35.

-

2

We find the focus on women in Albanian historiography, although not often, in several articles, where we will single out only a few of the last years: Lucia Nadin (2008). Albanians in Venice: Exile and integration 1479–1552. Tirana: 55; Teuta Shala-Peli (2015). Data on the role and position of women in Drisht and Shkodër during the Middle Ages. In Kosova (40, 36–47; Teuta Shala-Peli (2019). Dowry and gifts in arboretum families on the occasion of marriage: Second half of the 14th-15th centuries. In Kosova (44), 9–20; Georgios Giakoumis (2019). The social, cultural and pedagogical activities of the Moschopolitan guild of tailors (1714-1749). In Civilization of Voskopoja and century of Enlightenment, Ashak, 294–304 (in this article page 300 is of interest ); there are more articles about women in leadership positions, see for example: Albanian women: Forumi i grusa, Alban Tërbeshi (2023). national liberation in Kosovo (48), 115–121. While women in the history of the Second World War are treated more. See: Eli Krasniqi (2021) Same Goal, Different Paths, Different Class: Women's Feminist Engagements in Kosovo from the Mid-1970s until the Mid-1990s. In Comparative Southeast European Studies (69), 2–3, 313–334; Antonia Young and Jenna Rice (2012). De-centring the Albanian Patriarchy? Sworn Virgins and the Re-negotiation: of Gender Norms in the Post-Communist Era. In A. Hemming, G. Kera, E. Pandelejmoni (ed.) Albania: Family, Society and Culture in the 20th Century, Lit, 163–174.

-

3

The full text also brings an interesting case of a woman in Prizren in the century. XVIII. For more see Agron Islami (2020). Aspects of socio-economic and political life in Kosovo during the 18th century according to citizens' complaints and demands. In Kosovo (45), 51–66. The following footnotes are original to the author.

-

4

Halil Inalcik, Sûret-i Defter-i Sancak-i Arvanid, (Ankara: 1987); Selami Pulaha, Popullsia shqiptare e Kosovës gjatë shek. XV-XVI (studime dhe dokumente), (Tiranë: 1983); Ferid Duka, Shekujt Osmanë në Hapësirën Shqiptare (studime dhe dokumente), ( Tiranë; 2016), Iljaz Rexha, Venbanimet dhe Popullsia Albane e Kosovës (sipas Defterëve Osmane të shekullit XV), (Prishtinë: 2016).

-

5

Halil Inalcık, "Şikayet Hakkı: Arz-i Hâl ve Arz-i Mahzarlar", Osmanlı'da Devlet, Hukuk ve Adalet, (İstanbul: 2000), 48-51.

-

6

BOA.A.DVNSAHKR.d. 12/59, October 1764.

-

7

The document was found in the Ottoman archives by Agron Islami, who also translated it.

-

8

Agron Islami (2024). Educational development. In Pristina in history.

-

9

See Jashar Rexhepagiqi (1970). The development of education and the school system of the Albanian nationality in the territory of today's Yugoslavia until 1918. Prishtina: Textbook and Teaching Aids Agency. p. 115.

-

10

See Mara and Gjergj Brankovici (1411) Letter... in Documents.

-

11

Agron Islami (2024). The mosques of Pristina. In Pristina in history.

-

12

E. L. Lyon (1872) Notes on Albania in Documents.