The Gjinolli family is generally little known in historiography. In recent years, there have been a number of contributions in this regard, particularly about Maliq Pasha and Jashar Pasha, who are more well-known (even among historians).1 However, even in these articles, Abdurrahman, the last patriarch of this dinasty, is rarely mentioned. There is no biographical sketch for him, so here we will attempt to establish an initial framework, without claiming to have exhausted all relevant sources. In generally, not only was the historians interest low in the life of this personage, but also the archival records about him are scarcer than those for the other two predecessors.

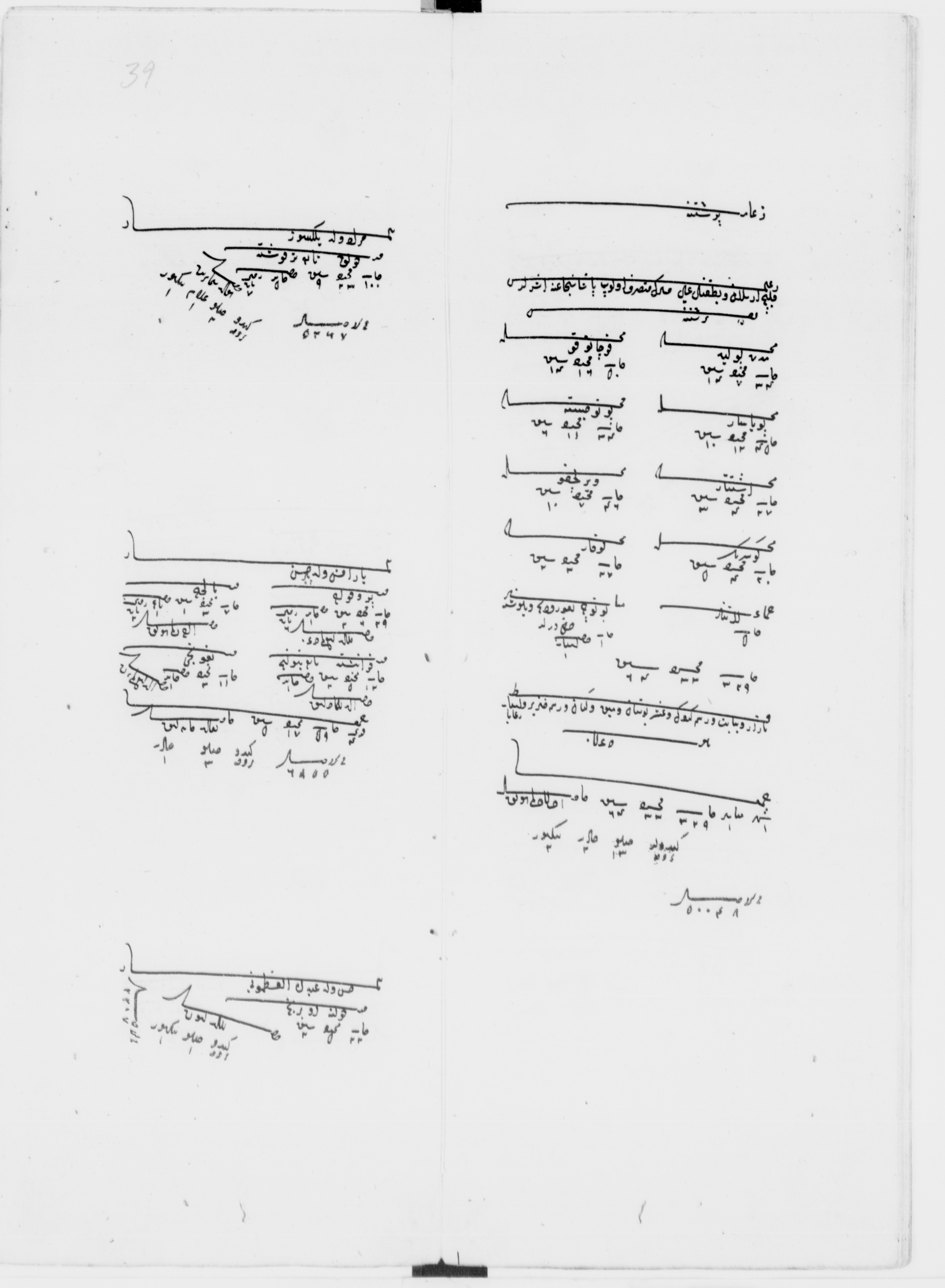

We have not seen any document (from those we had available) that confirms the birthdate of Abdurrahman Pashë Gjinolli; however, from circumstantial evidence, we can assume he was born around 1813.2 At least three archival documents confirm the claim that he was the son of Jashar Pasha, removing any doubt in this regard. The first traces of this pasha in the writings of the time appear in 1840,3 when he was appointed as the kaymakam (leader) of the Sanjak of Skopje, with headquarters in Prishtina.4 We know for certain that he held this position until he was dismissed on July 19, 1845.5 Sources are scarce during the time he carried out his administrative duties. The period we are discussing belongs to the years of the popular uprising (composed mainly of Albanians) that engulfed cities from Vranje to Skopje, including Prishtina, Vushtrri, Kaçanik, and Tetovo. In this wave of turmoil, Abdurrahman himself was also a target of insurgent attacks, as in at least one of their letters there was a demnad for his dismissal from the position of leader of Skopje and Prishtina.6 There is a case to believe that the Sultan initially supported the Pasha of Prishtina in this confrontation, as on August 7, 1844, he gave him a medal for his contribution.7 Meanwhile, in the population registration of Prishtina in 1844, Abdurrahman's name appears as a resident in the Great Mosque neighborhood, with extraordinary annual income for the time of 78,602 kuruş.8 A year later, after the uprising was already quelled, the Sultan dismissed him. He was briefly replaced by a Melek Bey, likely from Kumanovo, and then by a Hasan Bey, who held the position of kaymakam of Prishtina for a longer period. The name of this latter appears continuously from November 27, 1846, to December 11, 1850, about four full years.9

An illustration from 1872 showing a pasha in his guesthouse in Prishtina. It could be Abdurrahman Pashë Gjinolli.

An illustration from 1872 showing a pasha in his guesthouse in Prishtina. It could be Abdurrahman Pashë Gjinolli.

Abdurrahman himself was installed as the kaymakam of Prizren for a short time, about a year, again with headquarters in Prishtina.10 This appointment is a signal that despite his dismissal, his relations with the central administration in Istanbul had remained good.11 There are indications that he had a friendship with the former kaymakam of Prizren from the Rrotaj family. Abdurrahman was appointed to a post in Beirut on May 28, 1848, where he served as the chief commander, protector of the city for several years. In fact, it seems that he exercised this position outside of his headquarters in Prishtina, although his presence in his hometown seems to have been continuous. Moreover, for a few months between July and December in 1848, he returned as the kaymakam of Prishtina instead of Hasan Bey, but was dismissed again for disobedience regarding some tax matters. Hasan Bey was reinstated to this position. In June 1854, he was finally dismissed from the position of chief commander in Beirut. For several years after this, not much is known about his fate; it is only known that in 1855 he made a request to return to Prishtina regarding the settlement of some matters related to his properties in this city. Later, suddenly, in 1861, he reappears as the kaymakam of Prishtina, and also simultaneously as the kaymakam of Prizren. An important description from this time by two English travelers must be noted, which, among other things, speaks about his appearance, language, and background,

"Immediately on our arrival, the mudir12 of Prishtina sent to offer a visit, and then appeared, not as usual in the form of an obese and greasy-uniformed Osmanli, but as a gaunt Albanian in a green robe lined with fur. He was a fine-looking old man, with silver hair, glittering black eyes, a pale complexion, and with a look of blood unattainable to dignitaries who have earned promotion as a favourite pipe-lighter or café-gee. In a few minutes the companion of the mudir informed us that his superior came indeed of a noble race, and, as we displayed lively interest in the subject, the mudir himself took up the discourse, and told us the name of his family,13 adding that they were all Ghegga by race, and that in their country no one spoke a word of Turkish. Thus encouraged we proceeded to question him about other families of Northern Albania, and especially if he agreed with Consul Hahn’s informant that the greatest houses were those of Ismael Pasha and Mahmut Begola. He said they were great, but that the last sprout of one of them had taken service under the Sultan, adding contemptuously, "He is a humpbacked little fellow," and imitating the humpback."14

It is worth noting the expression that in “their country no one spoke a word of Turkish,” which undoubtedly is a significant testimony regarding the ethnic identity of the Gjinolli family — regardless of their devotion to the Ottoman Empire. However, it seems that Abdurrahman did not hold the position of mudir of Prishtina for very long the second time. Two years later, on July 30, 1863, he already appeared as a mutasarrif appointed to another place.15 Although, he had certainly served from Prishtina. Around 1869, he built a secondary school in Prishtina. He was married to a woman named Sanije and had sons named Zija, Ibrahim, Ali Danish, and Fuad.16 The exact date of his death is not recorded among the archival documents located in Prishtina. It must be after the year 1879, when he signed the statute of the League of Prizren as a delegate from Skopje.17

Bibliography

Islami, Agron (2021). “XVIII. Yüzyılda “Kosova”: Sosyo-Ekonomik Tarihi”. Stamboll: İstanbul Üniversitesi. [Disertacion doktorature]

Jaka, Ymer (1974). Një përfaqësi diplomatike e Napoleonit I në Prishtinë. Në Kosova, Prishtinë, f. 413–433.

Kaleshi, Hasan / Eren, Ismail (1972). Prizrenac Mahmudpaša Rotul, njegove zadužbine i vakufnama. Në Starine Kosova – Antikitete të Kosovës, (6–7), f. 24–60; Përkthyer në shqip te Edukata Islame, 2006 (81), f. 152–187.

Kırlı, Cengiz (2015). Tyranny illustrated: from petition to rebellion in Ottoman Vranje. Në New Perspectives on Turkey (53), f. 3–36.

Mackenzie, G. / Irby, A. (1877). Travels in the Slavonic provinces of Turkey-in-Europe. Londër: Daldy, Isbister and Co. (Botimi i pestë).

Mehmeti, Sadik (2004). “Sherh Rahati al-Kulub” e pir Muhamed Efendiut. Në Vjetari, Prishtinë, f. 497–501.

Nakiqeviq, Omer (1969). Revolti dhe marshi protestues i banorëve të Kosovës më 1822. Prishtinë: Arkivi i Kosovës.

Rexha, Iljaz (2016). Disa të dhëna arkivore për familjet mesjetare Gjinaj nga Novobërda dhe familjen fisnike të Jashar Pashë Ginollit si pasardhëse e tyre. Në Gjurmime albanologjike (46), f. 25–58.

Rugova, Yll (2024). Prishtina në histori: fragmente, dokumente dhe letra 1315–1905. Prishtinë: Varg.

Sheshum, Urosh (2020). Пашe из породице Џиноли (Џин-Огли) у 18. и првој половини 19. века. Në Serbian Studies (11), f. 11–40.

━━━ (2018). The role of Jazzar Pasha in the destruction of the sacral monuments on Kosovo (an example of tradition entersing historiography). Në Зборник Матице Српске За Друштвене Науке (168) 4, f. 849–872.

-

1

A biographical sketch for Malik Pasha and Jashar Pasha was built as early as 1972 by Hasan Kaleshi and Ismail Eren (khs. 2006, 157–158, 166), but this, although brief, is conveyed with great inaccuracy; We can find slightly more complete data in Rexha (2016, 26–58); And with fresher details and from Ottoman sources, two articles from Shoshum are important, one about Jashar Pasha (2018, 849–872) and the other about Gjinolli family in general (2020, 11–39). Important documentary information about Maliq and Jashar Pasha, but without any attempt at biography, can be found in the articles published by Nakicevic (1969) and Jaka (1974).

-

2

This assumption is based on the fact that it is known exactly when his father Jashar Pasha (1787–1846) was married, in October 1812 (cf. Jaka 1974, 418); from which at least a year later it can be assumed that his eldest son was born. This coincides with the date August 14, 1841, when he was appointed mytesarif of Skopje and Pristina, that is, somewhere around the age of 26, which is a relatively young age for a leader of such a level — but still very possible. He could hardly have been younger than that, which is why it is impossible to believe that he had a birthday later than 1813.

-

3

In general, in this short article, references from the Prishtina Archives are made to those copies of documents that have been brought from the Istanbul Archives, and which currently bear the same numbers as the original documents in Istanbul. We will refer to the numbers as they are, adding the name 'Arkivi i Prishtinës' in front.

-

4

Arkivi i Prishtinës, BOA. HAT. 326. 18986C.

-

5

Arkivi i Prishtinës, BOA. MVL. 67. 1266.

-

6

It is about an archival document in Istanbul to which the Turkish author Kirli (2015, p. 30) refers. The document is undated but refers to these events and can be assumed to have been sometime from June 1844.

-

7

Arkivi i Prishtinës, BOA. DH. 90. 4488.

-

8

At this time, an ordinary family had an annual income of around 500 kurush, while the richest person in Pristina had around 9,000 kurush a year. See Sarinay 2007, 378.

-

9

For the date of appointment cf. Arkivi i Prishtinës, BOA. MVL. 82. 1628. Courses for the date of discharge cf. Arkivi i Prishtinës, BOA. MVL. 235. 4.

-

10

He had taken the new position on July 21, 1846, cf. Arkivi i Prishtinës, BOA. A. TIF. 1.94.

-

11

Abdurrahman Pasha also had good relations with the governor of Skopje, Mehmet Selim, who on February 26, 1846 made a request in Istanbul to find a new position for the dismissed Abdurrahman Pasha. See Arkivi i Prishtinës, BOA. A. MKT. 36. 62.

-

12

Although in the archival document that we quoted Abdurrahman Pasha is referred to as kajmakam, it is very possible that during this time the position of the head of Pristina was that of a simple mudiri, that is, head of the kaza. The exact date of their visit is not given, but the text of the visit to Kosovo itself was written in August 1862 in Sofia. Renaming, AP. A.MKT.UM. 482/73, year 1861.

-

13

In this fragment, the name of the family is never given, even though it is clear that this name was known to the authors.

-

14

Cf. Mackenzie and Irby 1877, 193–234. For a more extended fragment, see the section of documents in Prishtina in History.

-

15

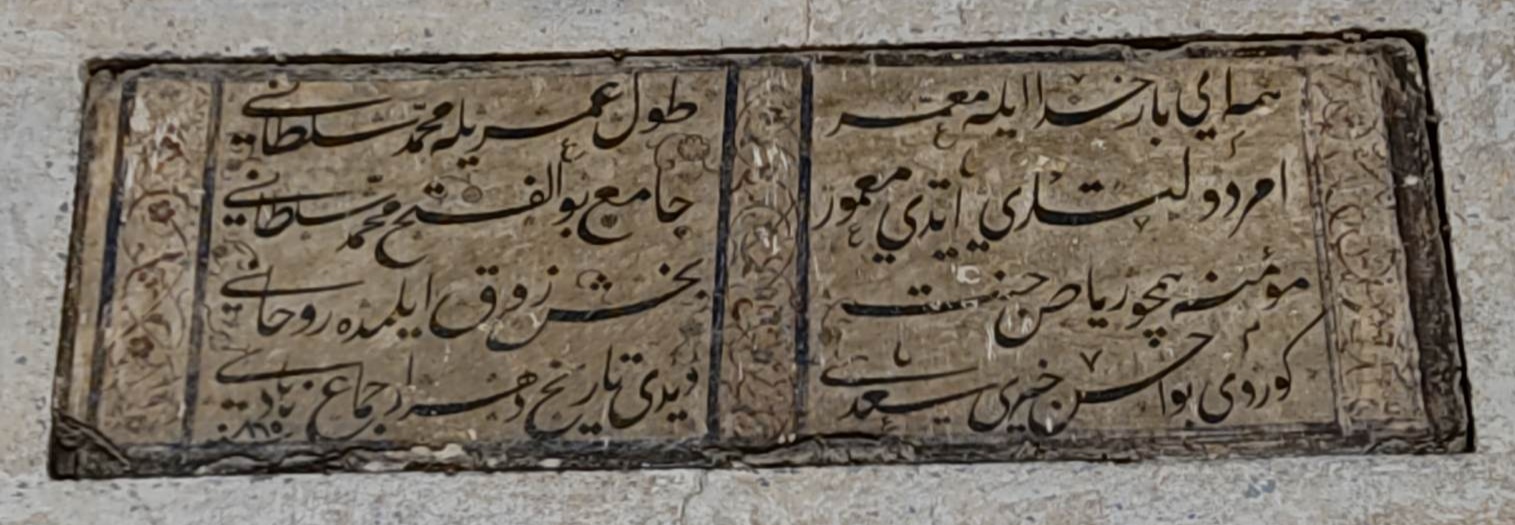

Arkivi i Prishtinës, BOA. A. MKT.MHM. 271. 63. It seems that in the last part of his life he served as the mayor of Serres, near Thessaloniki in Greece. A colony of Prishtina Albanians there is also evidenced by an inscription in a book located in the Kosovo Archives (cf. Islami 2021, 171; Mehmeti 2004, 497–501).

-

16

In 1872, "the former mayor of Sirroz, Abdurrahman Pasha", khs. Archive of Pristina, BOA. MF. MKT. 6. 21.

-

17

"Abdurrahman Siri (Delegat i Shkupit)" (Cf. Rugova 2024, 133).